Political science, paradoxically, is both a very old and relatively recent discipline. Its origins go back to antiquity in classic European or Asian thought as far as recorded history goes. As an independent and respected academic field, however, it came into being in most countries only after World War II. This is due in part to the fact that its subject matter had been addressed by neighboring disciplines like philosophy, history, and public law, but also because it requires, more than others, a “breathing space” of freedom of thought and expression that is not voluntarily granted by most authoritarian regimes and that has developed worldwide only with decolonization and recent waves of democratization.

This article surveys the discipline of political science, beginning with an analysis of politics itself. Two important definitions of politics are discussed in detail here. First, politics can be viewed as a means, either for maintaining social harmony or for achieving a supreme good, as in some religious conceptions of the state. Second, politics has been understood as an instrument by which a central institution or a legitimate authority exercises power. The next section of the article examines the epistemological foundations of the discipline of political science. The third section traces the growth of political science during the 20th century and examines its evolving relationships to other social sciences and to other fields, most notably law and philosophy. The final section of the article describes more recent developments and perspectives in political science, as it has become a dynamic discipline with its own identity and with participation from political scientists around the globe.

Contents

- Politics

- Epistemological Building Blocks of Political Science

- Political Science Relations with Other Social Sciences

- Recent Developments and Perspectives in Political Science

- References

Politics

Politics as a Special Sphere

The concept of politics carries different meanings. It can be considered to be an art (scholars are “studying politics”); an activity (one can “play politics” in one’s office, in one’s club, even in one’s family); a profession (some “go into politics”); or a function (“local politics,” “national politics”). Most political scientists consider the first meanings as derived from the last one, even as metaphoric, while some others have a wider and more abstract conception that is broader than that of function. Politics also has been understood as both to polity, which refers to an organization (a state, a regime and its constitution) and to policy, which refers to a system of political decisions and specific subfields (like health, education, foreign relations) through organizations act to carry out their functions. In a comprehensive perspective, politics is thus considered to be linked to a function, a system, an action, and a behavior.

All of them are, however, connected to a special dimension of the history of humankind. Even if some scholars object that some societies ignored politics (Clastres, 1975), most anthropologists consider politics as a constant of the human condition. In the first part of this entry, this constant will be grasped in its various definitions, and then it will be inserted into the general social order. The following sections examine definitions of this constant as a function and as an instrument.

Politics as a Function

Politics can be conceived as a contribution to the social adventure, as a function of the social order, or, quite differently, as a distinctive instrument, a special way of action. The first approach is more classic and deeply rooted in the various philosophical traditions that were elaborated around the world, while the second one is modern, related to the rise of positivist theory in the social sciences. In this section, we consider two ways in which politics can be seen as a function.

Politics as a Function: Promoting Social Harmony or Supreme Good?

Many philosophers have located politics in the art of coexistence. If human beings are selfish by nature, as they are often conceived, but must live and grow up together, to create peaceful coexistence is obviously one of the main functions of the polis. As such, politics should be considered as the permanent invention of the polis (city), as the construction of each social unit that aims to keep people together on a permanent basis. This point was already made by Plato, who considered politics as the art of organizing social harmony. We also find it in other traditions. Islam conceives of politics as a weakly differentiated function that aims to overcome tribal fragmentation through the principle of unity (tawhid). As such, tawhid will be achieved through the absolute Unity of God, and so politics cannot be entirely accomplished without religion: Politics cannot be conceived as a differentiated structure, but it is obviously a social function. The same principle can be found in Hindu writings. The Arthasastra (3rd century BC) and the Manusmriti (2nd century BC) were written during periods of decay and so-called evil, which implied starvation, violence, and chaos, while the Mahabarata covered a much longer period (from 1st millennium BCE to the 5th century BCE). Here, politics is presented as an absolute requisite for keeping peace and order, even if the tradition oscillates between divine invention in politics (Manusmriti) and its contractual origin (Mahabarata). In its turn, the Buddhist vision stresses the entropy of the world that leads to inequality, sexual division, property, and thus to conflicts and lack of safety. The orientation of this reform of Hinduism prompts human beings to choose a king as a guarantor of the social order. Similarly, Confucius pointed out that men need a ruler for preventing disorder, disturbance, and confusion.

This first function, promoting social harmony, obviously shaped political philosophy to a large extent up to the present day. Social contract theory clearly emanated from this postulate, in the Islamic tradition (mithaq, bay’a) as well as during the European Enlightenment. The Arthasastra anticipated Thomas Hobbes’s vision of the state of nature, when it described the lack of politics as resulting in evil and vices, or when it mentioned the fable of the big fish that will eat the small one (Matsyanyaya). The functional dimension of politics, as the art of coexistence and “maintaining harmony,” can, therefore, be considered as really transcultural and common to the humanity’s different histories. Here, we can probably locate the roots of a pluralist vision of politics, as this first definition paves the way for a plural conception of the city (polis) where people do not necessarily share the same interests, the same beliefs, or the same ethnic characteristics. Quite the opposite, in this perspective, diversity is the real raison d’être of politics.

However, politics also claims a second function, which is more demanding and sophisticated. Some philosophers and thinkers are going further, beyond the invention of the city, pointing to another purpose: Politics is supposed to lead to the path of righteousness, to promote virtue, and to enable humans to achieve the Supreme Good. Thus, Aristotle conceived of politics as referring to welfare and virtue. The city must be constructed as the good city: Political science is elevated then to something much more demanding, namely, the “science of the good politics” or the “science of good government.” This vision can be found in Islam through the commitment to divine law (sharia); when taken to its extreme, this conception even becomes a way of challenging power holders and leads to a political inversion in which protest is a more important political activity even than governing. In the same way, the Arthasastra describes politics as promoting peace and prosperity, while Buddhism produces an ethic of human behavior. Confucianism also gives the central role to the virtue that humans naturally possesses, but that is achieved through the ruler and his norms.

These two functions of politics convey the two faces of political theory, one of which is positivist, the other normative. If politics is only the science of the city, it is first of all a behavioralist science. If it is the science of the Supreme Good, its normative orientation is dominant. This tension has partly been overcome by an instrumentalist approach to politics, according to which the distinguishing nature of politics has to be found in the instruments used for running the city instead of its ultimate goals.

Politics as an Instrument: The Science of Power?

Power—in Max Weber’s sense as the ability to achieve your interests even against someone else’s will, that is, as coercion—is understood here as the first instrument through which politics operates. All major thinkers claim that the city cannot exist without power, no matter how it is structured. There is thus a long tradition of connecting power and politics, in which political science is assigned to study how power is formed, structured, and shared (Lasswell & Kaplan, 1950). However, the science of politics and a science of power are not synonymous: Is every kind of power necessarily political, for example, in a firm or a club? In a broader sense, some authors state that politics can be played in an office or inside a family, but this expression is merely a metaphor when conceived in a micro-social order. Conversely, if we consider power as the essence of politics, we have to opt for a wide definition of power that includes ideology, social control, and even social structures, and thus deviates from a vision of power as purely coercive.

For this reason, politics is commonly defined as a specific kind of power; either it is held by a central institution, such as a state, a government, a ruling class, or it is used by a power holder who is considered to be legitimate. The first perspective approaches politics as the science of the state and implies that traditional and weakly institutionalized societies lack the centralized power that is necessary for politics to exist. The second promotes the concept of legitimate authority as the real essence of politics and suggests that in this sense politics is more evident in democracies than in than authoritarian or totalitarian systems.

Some visions also link power and norms. Pushing the Aristotelian definition further, they define politics as the set of norms that lead to the City of Good—either the City of God or the City of the Philosopher. This radical conception is to be found in several traditions: that of Augustine, rather than Thomas Aquinas, in the Christian culture; Puritanism with the Reformation and Calvinism; radical Islam in the perspective of Ibn Taimyya. This conception, however, runs the risk of drifting into totalitarianism or at the very least depreciating the political debate, as it make any kind of political choice impossible.

The connection with territory is also frequently used as an instrumental approach to politics. The Greek tradition paved the way when Aristotle stressed the difference between politics, ethnos, and oîkos (household). If politics is conceived as the coexistence of diverse peoples, it denies that there is such a thing as “natural territory” and implies a socially constructed territory as its required arena. That is why Max Weber makes territory a key element of his definition of politics. For Weber, a community has a political quality only if its rules are granted inside a given territory: this territorial invention hardly fits nomadic societies or even a number of traditional ones (Evans-Pritchard, 1940). But even if it gets close to a state vision of politics, it emphasizes the role of pluralism and diversity inside the political order. In a more extensive conception of the spatial dimension of politics, public and private spheres are opposed: the former is seen as the natural background of political debate, while the latter is conceived as a resistance against political power and its penetrations (Habermas, 1975). We also find again the possible opposition between religious and secular spheres (other-worldly/this-worldly), and even the disenchantment with the world as one of the possible sources of politics.

After going through all these definitions, the criterion of social coexistence seems to be the most extensive one, and probably the least questionable. If politics is everywhere around the world considered more or less as managing social harmony, it can clearly be conceived as the opposite of some other classical spheres of social action (politics vs. social life, military, administration, etc.). As such, it is part of the general social arena, as an ordinary social fact, but a very specific one.

Politics in the Social Division of Labor

Here we face a contradiction that is shaping a serious debate among political scientists. If the conception of politics as an ordinary social fact tends to prevail, political science merges with political sociology (see below). In the opposite version, the latter would be defined as a part of political science, sometimes with ambiguous borderlines. The vagueness and the mobility of the borderline stem from different factors: the diversity of the great theories in the social sciences, which do not reflect the same visions of politics and which are torn between power and integration; the historical and cultural background of politics, which is shaping different kinds of lineages; and the present impact of globalization, which is probably fueling a new definition of politics that is increasingly detached from concepts of ethnicity and territoriality.

Two Traditions: Power Versus Integration

Max Weber is obviously considered as a “founding father” by both sociologists and political scientists. He clearly promoted a political vision of sociology when he developed his two major concepts of Macht (power as coercion) and Herrschaft (power as authority). Both of them can be found in the very first steps of his sociology where he defines power as the ability of one actor in a social relationship to modify the behavior of another, through pressure, force, or other forms of domination. From a Hobbesian perspective, power plays the major role in structuring social relationships, while the social actors strive to give meaning to this asymmetrical relationship in order to make it just and acceptable, thus establishing the legitimacy of those with power.

In modern society, the state plays an important role and politics has an exceptional status, as it is theoretically conceived as the main basis of social order. This conception is also strongly rooted in the Marxist vision, where the state is considered the instrument by which the ruling class maintains its domination, as the bourgeoisie does in the capitalist mode of production. Carl Schmitt also starts from a Weberian presupposition in linking politics to enmity. By contrast, in a Durkheimian vision, integration is substituted for power as the key concept. Politics is conceived neither as an instrument of domination nor as a way of producing social order; rather, it is a function by which the social system is performing its integration. Obviously, this function implies institutions and then a political sphere, including state and government, but it is considerably more diffuse and appears to be produced by the social community and its collective consciousness. From this perspective, a political society is made up of social groups coming together under the same authority. Such an authority derives from the social community and the collective consciousness; it is constituted by rules, norms, and collective beliefs, which are assimilated through socialization processes. As such, politics is closely related to social integration and is supposed to strengthen it further. That is why there is a strong correlation between a growing division of labor, from the increasing political functions, and their differentiation from the social structures. “The greater the development of society, the greater the development of the state” (Durkheim, 1975, 3, p. 170). Durkheim contrasted “mechanical solidarity” arising because of perceived similarities among people (e.g., in work or education) from “organic solidarity” arising when people are doing different things but see themselves as part of an interdependent web of cooperative associations. This Durkheimian vision is to be found later in the functionalist and systemic concepts of political science as elaborated by Talcott Parsons, David Easton, Gabriel Almond and others, but also in the socio-historical traditions, which attempted to link the invention of politics to the sociology of social changes, as in the work of Charles Tilly or Stein Rokkan. It is also congruent with the social psychological paradigm, which tries to capture politics through its social roots, such as socialization, mobilization, and behavioral analysis.

By contrast, state and power are the real sources of a Weberian political science. Politics is no longer a function of the division of labor, but has definitely its own determinants. Quite the opposite, social history is considering the transformations in the mode of government and more precisely the mode of domination. Power is thus conceived as an explanatory variable of the transformation of societies and political orders. Such a vision is common among those approaches of political science that are centered on power politics, the role of the state, or the nature of political regimes or that are focusing on political institutions and the conditions of their legitimization.

The Diversified Lineages of Politics

Politics is thus approached in different ways, but is also intrinsically plural. During the 1970s, when globalization began to shape the world and when decolonization was completed, both history and anthropology incorporated the perspective of politics with respect to plurality. This perspective on plurality also challenged the mono-dimensional vision that had been promoted by developmentalism a decade earlier. In anthropology, Geertz (1973) pointed out that politics covered several meanings that are changing along historical lines and according to specific cultures. These meanings are socially constructed as human actors encounter different kinds of events, challenges, or goals and as they are rooted or embedded in different sorts of economic and social structures. Politics is understood as achieving the will of God and his law in Islam, while it aims to manage the human city in this world according to the Roman Christian culture. The first conception was fueled by Muhammad’s hijra when the Prophet left Mecca because of opposition to his teaching and went to Medina to build up the City of God. The second conception was shaped by the Roman experience of religion, which survived during the centuries of the Empire and had again to survive when the latter collapsed during the fifth century. In this dramatic contrast, politics does not cover the same meaning, as it is differentiated from the public sphere and oriented toward individuals in the Roman tradition, while it was more globally constructed in the Muslim tradition. In both cultures, this diversification continued; as Geertz mentions, politics does not have the same meaning in Indonesia and in Morocco, two Muslim societies that experienced greatly different histories.

For that reason, politics can be properly defined only when the definition includes the meaning that the social actors usually give to it. This cultural background implies a huge empirical investigation, which is all the more difficult since the observer tends to view things through his or her own concepts, which are obviously culturally oriented. The risk, therefore, is high to consider as universal a cultural vision of politics, which shapes the paradigm of empirical political science. Translations can be particularly misleading and even fanciful. For instance, the Arabic word dawla is often translated as “state,” whereas their meanings are hardly equivalent. It is quite impossible to convey, through translation, the deep cultural gap that really implies two competing visions of politics. The only way of going ahead is to deepen the anthropological and the linguistic investigations in order to identify distinctive features of each conceptualization of politics, following the “thick description method” recommended by Geertz. But is there any end to this “individualization” of politics? To be operative, research must postulate a minimal universality of its own concepts and contain the risks of “culturalism”: It has to keep the connection with history and anthropology while remaining in a universalist framework.

A Politics of Globalization

This dilemma is revived and even stimulated by the globalization of the world. In the new global order, politics is no longer limited or contained by the territoriality principle. It becomes reinvented beyond the classical coexistence of sovereign cities. Politics cannot be conceived as a simple addition of social contracts, as it was in the Westphalian paradigm. This challenge is first posed to the “realist” theory of international relations, questioning the absolute opposition between “inside” and “outside,” or “domestic politics” and “international politics.” The latter is no longer confined to the dialogue of sovereigns and has destroyed the traditional categories and criteria of politics. After all, is there a “global covenant,” as Robert Jackson (2000) argues, that totally reshapes the construction of politics?

The hypothesis that competition among nation-states can be understood as parallel to that within nation-states supported the extension of the concept of politics to the international sphere. The idea of power politics was projected into the international arena in order to stress that international politics referred to the classical grammar: States, like political actors, were competing according to their own interests and were primarily concerned with their ability to dominate other states, or, at least, to contain the power of the others. Morgenthau (1948) defined international politics as the “struggle for power,” power as “the control over the minds and actions of other men,” and political power as “the mutual relations of control among the holders of public authority and between the latter and the people at large” (p. 27).

Although this conception is clearly rooted in a Weberian approach to politics, it does not belong only to the past. But it neither covers nor exhausts all the political issues at stake in the new configuration of the international arena. First of all, as sovereignty is fading, the proliferation of transnational actors no longer restricts international politics to a juxtaposition of territorial nation-states. Second, power and coercion are losing their efficiency as influence and social relationships are getting more and more performance oriented. Third, globalization and the growing international social community are shaping common goods, creating a kind of community of humankind; human beings are then creating “a political dialogue that can bridge their differences . . . without having to suppress them or obliterate them” (Jackson, 2000, p. 16). We are here rediscovering Aristotle when he claimed that men need each other for their own survival.

Nevertheless, no one would assert as yet the complete achievement of an international society or an international community. International politics remains an unstable combination of references to power politics and to international social integration: It then confronts the vision of politics as coexistence among diversity. It goes back to the idea of harmony, but without a completed contract, to the hypothesis of a global city without a central government, to the assertion of common norms without binding measures. This combination is at the core of the English School of international relations that refers to the “anarchical society.” But it is also close to the French vision of an international solidarity. In the end, politics gets closer and closer to a functional vision of managing social diversity in order to make it compatible with the need for survival.

Epistemological Building Blocks of Political Science

Some major building blocks of political science can be identified that help characterize some common elements in existing approaches, but also, and perhaps more important, enable us to locate these positions and their differences more precisely with regard to the major epistemological foundations. The first of these building blocks concerns the multidimensionality of our subject matter; the second, its plastic and malleable character and the resulting self-referential problems; the third refers to a systems perspective of politics; and the fourth to the linkages between different levels (micro-, meso-, macro-) of political (and more generally social) analysis.

Multi-Dimensionality

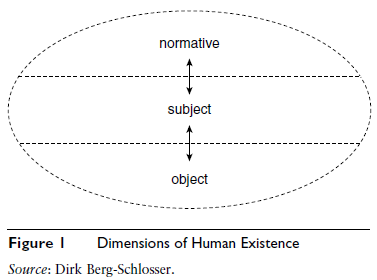

The most basic distinctions of our discipline, which distinguish it in some important respects from the “natural” sciences, concern the dimensions of its subject matter. As in nature, there are certain hard “objects” such as political institutions and social structures, which can be identified and which are “tangible” and observable in certain ways. In addition, however, there is a “subjective” dimension in which such objects are perceived by individuals and groups and translated into concrete actions. Such perceptions themselves are shaped by a number of psychological, social, or other factors. This distinction is commonly accepted and runs through the history of philosophy from antiquity to the present day and concerns all sciences of humankind, including medicine. There, distinctions between body and mind (or consciousness) and the subsequent divisions into subdisciplines such as anatomy and psychology are commonplace. Similarly, the fact that there are possible interactions between these dimensions is well accepted, even though in medicine some of these psychosomatic relationships are still not well researched. The third dimension, the “normative” one that concerns ethical judgments of “good” or “bad” actions and behavior, is more problematic. In medicine, again, some ethical norms have been generally accepted since the time of Hippocrates, but debates continue about, for example, when exactly human life begins or ends, and what the respective theological or philosophical justifications are for such positions. In philosophy, this “three-dimensionality” of human existence has also been elaborated by Immanuel Kant, for example, in his Critique of Pure Reason (1787/1956, p. 748 ff.).

A graphical representation of these dimensions can be rendered in the following Figure 1 (where the dotted line represents a “holistic” position):

The crux of the matter really concerns problems of distinguishing such dimensions and their interactions not only analytically but also in actual practice, and controversies about normative, ontologically based justifications and their respective epistemological and methodological consequences persist. Here, we cannot go into these debates in any detail, but we find it useful to locate the major emphases of the current meta-theoretical positions in political science with the help of such distinctions. Thus, the major ontological approaches have their basis in the normative dimension ranging from Plato to Eric Voegelin or Leo Strauss, but also concern attempts in linguistic analysis (e.g., Lorenzen, 1978), or communications theory (Habermas, 1981). This also applies to non-Western traditions such as Confucian (Shin, 1999), Indian (Madan, 1992), or sub-Saharan African (Mbiti, 1969) ones.

Sharply opposed to such foundations of political theory are critical-dialectical or historical-materialist positions in the tradition of Karl Marx and his followers. There, the object dimension of the modes of production and re-production of human existence is the basic one from which the others are derived. Thus, the objective social existence determines the subjective consciousness and the political and normative superstructures. On this position, the teleological theory of history of Marx and his followers from the early beginning until the classless society and its peaceful end is based as well.

The third major meta-theoretical position, a behavioral or behavioralist one, takes the subjective dimension as its starting point, expressing a position of methodological or phenomenological individualism (for the use of these terms, see Goodin & Tilly, 2006, p. 10ff.). Then subjective perceptions and subsequent actions of human beings are what really matters. These shape social and political life. This position has been most influential in election studies, for example, but also concerning some aspects of political culture research. In a somewhat broader perception, both subjective and objective dimensions and their interactions are considered by empirical-analytical approaches, but, from a positivistic point of view, no normative judgments can be made on this basis. Long-lasting controversies concerning this position go back to Max Weber and his followers but are also reflected in more recent debates between Karl Popper and Jürgen Habermas, for example (see Adorno et al., 1969).

These basic meta-theoretical positions and their variations remain incompatible. Similarly, whether these dimensions can in actual fact be separated or, by necessity, always go together from a holistic perspective remains controversial. The latter position, in contrast to Kant, is, for example, represented by G. W. F. Hegel, but also by Marx and some of his followers (e.g., Lukács, 1967). In the same way, epistemological positions based on religion, including Buddhism and Confucianism, perceive these dimensions in a holistic manner. From a more pragmatic perspective, it seems that the fundamentalist debates about such matters have subsided in the last few decades and most political or social scientists just agree to disagree about such basic ontological or religious positions and their respective justifications. Nevertheless, Figure 1 may help better locate such positions and to put some conceptual order into these controversies.

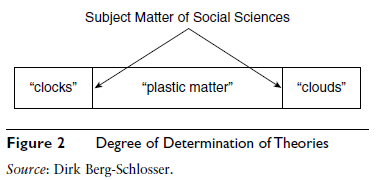

The Plastic Matter of Political Science

As a result of the change from Newtonian physics with its deterministic relationships to quantum theory and probabilistic relations in nuclear physics, Popper (1972) has coined the metaphor of “clouds and clocks.” Clocks represent Isaac Newton’s deterministic world, as in astronomy, for example, where the movements of stars and planets or the next solar eclipse can be predicted (or retro-dicted) with clocklike precision. Clouds, by contrast, constitute a very elusive substance, the structures and regularities of which cannot easily be grasped over a somewhat longer period even today by the most advanced computers of meteorologists and their satellite-based data. Between these two extremes, however, which should be perceived as the opposite poles of a continuum rather than mutually exclusive positions, there is a plastic matter that is malleable in the course of time and that is neither perfectly determined nor subject to pure chance.

In an important essay, Gabriel Almond and Stephen Genco (1977) have transferred this concept to the social sciences and politics. They state that

the implication of these complexities of human and social reality is that the explanatory strategy of the hard sciences has only a limited application to the social sciences. . . . Thus, a simple search for regularities and lawful relationships among variables—a strategy that has led to tremendous success in the physical sciences—will not explain social outcomes, but only some of the conditions affecting those outcomes. (p. 493)

The deductive subsumption of individual events under “covering laws” in Carl Hempel’s (1965) sense, according to which claims about individual events can be derived deductively from premises that include a scientific law, thus is not possible for the most part. In addition, factors of human choice and action plus, possibly, some elements of pure chance in certain conjunctures also have to be considered.

As a consequence, we have to be more modest in our claims about the precision of causal relationships, the generalizability of regularities, and the universality of theories. At best, therefore, only theories located more precisely in time and space—what Robert K. Merton called “medium-range theories”—seem to be possible for most practical purposes. Such a view also corresponds with a position already expressed by Aristotle, who located politics in an intermediate sphere between the necessary, where strict science can be applied, and the realm of pure chance, which is not accessible for scientific explanations.

Such distinctions are illustrated in Figure 2:

Again, the full implications of such a perspective cannot be discussed here, but this figure should be helpful, once more, to locate some of the “harder” and some of the “softer” approaches in our discipline along this spectrum. On the whole, we would agree with Almond and Genco’s conclusion that

the essence of political science . . . is the analysis of choice in the context of constraints. That would place the search for regularities, the search for solutions to problems, and the evaluation of these problems on the same level. They would all be parts of a common effort to confront man’s political fate with rigor, with the necessary objectivity, and with an inescapable sense of identification with the subject matter which the political scientist studies. (p. 522)

The last point also leads to the next differentia specifica of the social sciences as compared to the naturalist sciences and their distinct epistemology.

Self-Referential Aspects

This sense of identification also can be seen in different ways. First of all, it means that as human and social beings we are inevitably part of the subject matter we are studying. Even if we attempt to detach ourselves as much as possible from the object under consideration some subjective influences on our perception remain. These can be analyzed by psychology, the sociology of knowledge to discern our (conscious or unconscious) “interests” in such matters, and so on, but some individual “coloring” of our lenses seems inevitable. Therefore, a certain “hermeneutic circle,” which should be made conscious and explicit in the interactions with others, remains (Moses & Knutsen, 2007, Chapter 7).

However, this limitation can, again in contrast to naturalist perceptions of science, be turned to one’s advantage. As human beings we can empathize with each other and can intersubjectively, if not objectively, understand and interpret the meaning of each other’s thoughts and actions. This is even more the case when we are trained as social scientists in a common methodology and scientific language. This latter point also distinguishes the perception, level of information, and theoretical interpretation of a political scientist from the “man (or woman) in the street” talking politics, in the same way that a meteorologist has a different knowledge of what is happening in the atmosphere compared to the daily small talk about the weather. Nevertheless, such inevitable subjectivity, which is also historically and culturally conditioned, opens the way to more pluralist interpretations and meanings. Constructivist approaches, as contrasted to naturalist ones, can dig deeper in certain ways into this subjectivity and the plurality of meanings (cf., e.g., Foucault, 1970).

Two more points concerning our identification with the subject matter and our self-referential position within it must be mentioned. Being part of the substance, we can also, consciously or unconsciously, act upon it. Thus, self-fulfilling or self-defeating prophecies become possible as feedbacks between the interpretation or even just personal opinion of an important actor or social scientist whose authority in a certain sphere has become acknowledged in the matter he is dealing with. This frequently occurs when some “analysts” give their opinion on probable developments of the stock exchange or currency rates and many people follow suit. This also applies to electoral predictions with respective bandwagon and underdog effects.

Finally, being part of our world and being able, to some extent, to act on it, also raises the question of social and political responsibility. This brings us back to the normative side of politics with which we inevitably have to deal, self-consciously and being aware of possible consequences. In this respect, too, a recent constructivist turn in the theory of international politics, in a somewhat more specific sense of the term, has led to the broader discussion and possible acceptance of more universal norms.

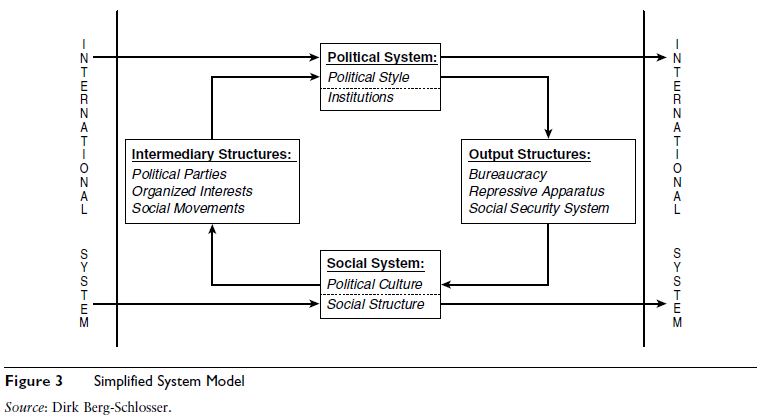

A Systems Perspective

Within this multidimensional, malleable, and dynamic universe more specific political elements can be identified. One difficulty in this respect, again, lies in the contrasting meta-theoretical positions and their perspectives on politics (see the first section above). In a more abstract way, politics can also be conceived as the regulating mechanism in large-scale modern societies. Easton (1965) thus defines politics as “the authoritative allocation of values” in society and the forces shaping these procedures. In this process, different elements interact in a systemic way regulating conflicts. This mechanism can be conceived like a thermostat with the respective inputs and outputs connected by an effective feedback procedure in a cybernetic sense (see also Deutsch, 1963). Such relationships can be illustrated in a simplified system model (see Figure 3).

This system model should not, however, be equated with systems theory in a more demanding sense (e.g., Luhmann, 1984). Thus, such systems need not necessarily be in equilibrium and they may also explode or implode as, in fact, they did in Communist Eastern Europe.

Nevertheless, such a model is again helpful to locate the major subdivisions of politics (and political science), which also constitute the major subsections of this encyclopedia and, in fact, many political science departments or national associations. The bottom square includes, in a broader sense, the fields of political sociology and, when this is treated separately, political economy. The square on the left-hand side represents political sociology in a narrower sense of the term (organized interest groups, political parties, etc.). The top square reflects the institutional side (involving a possible separation of powers, etc.) but also questions of governance often including the realm of public policies and public administration on the right-hand side. All this is embedded in the international system concerning interactions with the outside world both of state and society as the field of international politics and, in a more limited sense, international political economy. The arrows of such interactions can go in both directions. The systematic comparison of such systems or some subfields is the realm of comparative government. Overall theoretical (and philosophical) implications are the concern of political theory, and the respective methods and analytic techniques applied constitute the subfield of political methodology.

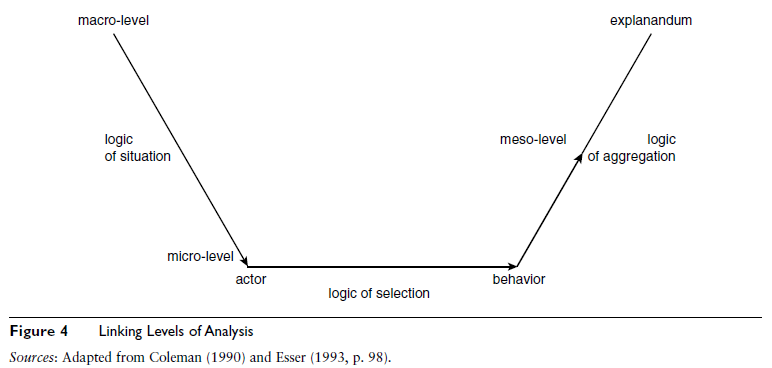

Linkages Between Levels of Analysis

A final building block to be considered here concerns the links between macro-aspects of entire political systems and their relationship with the micro-world of individual citizens and the meso-level of organisations in between. For this purpose, what has been dubbed “Coleman’s bathtub” (Coleman, 1990, p. 8) is most helpful. Here, a given objective (structural) situation at the macro-level (on the upper-left-hand side in Figure 4) can be linked to the micro-level of individual subjective perceptions and values, which are then translated into concrete actions, possibly aggregated on the meso-level, and then leading to the outcome on the macro-level to be explained (upper-right-hand side). This relationship is illustrated in Figure 4.

It is important to note at this place that we do not imply for the individual actors, as is done for example in economics and rational choice theory, a specific logic of selection, as, for example, maximizing a person’s material well-being. Such very restrictive assumptions of “homo oeconomicus” or even “homo sociologicus” (Dahrendorf, 1977) only rarely apply in political science, where usually a much wider range of choices exists, even if some of which may appear as “irrational” to others (for example, strongly felt ethnic or religious identities).

The purpose here, again, rather lies in the possibility to locate various approaches and their respective assumptions in such a scheme and to show the plurality of concepts that can be integrated here, but keeping them in a coherent relationship. Hartmut Esser (1993, p. 23 ff.), for example, has extended possible assumptions at the micro-level to include “restricted, resourceful, evaluating, expecting, maximing men” (RREEMM) or women, and even further assumptions about conflicting “identifying” (with some collective entities) or “individualizing” attitudes (RREEIIMM) or similar ones may be added. For the logic of the situation also framing procedures play a role where individual perceptions are shaped by the social milieus of one’s childhood and later environment (see also D’Andrade, 1995). The point here is to show that in this way given historical and traditional constraints at the macro-level terms can be meaningfully linked to individual and, at the aggregated level, collective political action. Which particular historical, cultural, or other factors condition these choices in any given situation can be left open at this place, leaving room, again, for a plurality of cultural and theoretical perspectives.

The Need for a Reflective Pluralism

As this overview has shown, there are some basic building blocks, which can be usefully employed in a variety of ways for locating different epistemological positions and historical-cultural traditions in political science and similar fields. In this way, it at least becomes clearer where (and perhaps also why) certain contending positions actually differ. We do not intend to “harmonize” these positions. They all have, to varying degrees, their respective strengths and weaknesses, and no coherent, well-integrated theoretical building is constructed here with these blocks. That may even not be desirable, leaving some room to agree to disagree about some basic issues and perspectives. What is desirable instead is to elevate our consciousness and our way to deal with such controversies to a level of reflective pluralism, where not just anything goes, but where contending epistemologies and approaches can be brought into a fruitful interdisciplinary, intercultural, and, possibly even, meta-theoretical dialogue.

As already mentioned, political science has always been characterized by a diversity of contending meta-theoretical positions, paradigms, and approaches. In Europe, in the last century various strands of normative-ontological, Marxist, and empirical-analytical persuasions have been at the forefront (for such and similar terms see, e.g., Easton, Gunnell, & Graziano, 1991; Quermonne, 1996). For several decades in the United States, “behavioralist” positions and, more recently, “rational” and “public choice” approaches have dominated (cf. the influential volumes by King, Keohane, & Verba, 1994, and Brady & Collier, 2004). In other parts of the world, different theological, philosophical, and epistemological traditions have influenced the (more recent) emergence of political science there. Altogether, thus a great variety of contending positions, which have been summarized as “naturalist,” “constructivist,” and “realist,” can be observed (Moses & Knutsen, 2007).

Political Science Relations with Other Social Sciences

Pluralism and different traditions in political science also emerge when we change perspective and focus more precisely on its relationships with other social sciences. This section explores three sources of political science as it differentiated itself from other disciplines.

Evolution of Political Science

When looking at the period after World War II, the basic difference in the traditions of different countries and areas of the world is between a plural form (political sciences) that is more common in Europe and encompasses the singular (political science). Conversely, in the tradition of United States the singular form (political science) includes the plural (political sciences). In the singular, there is a pluralist political science where empirical analysis is dominant, but also other perspectives (law, history, philosophy) are present. However, be it plural or singular, during the last decades empirical political science has increasingly differentiated itself from sociology, and above all from political sociology, public law, political philosophy, and contemporary history. Actually, in these developments we can see differences among disciplines or, more precisely, among specific groups of scholars in specific countries, but also overlapping and mutual influences with ever stronger interactions among scholars who are able to cross borders from Europe to North and South America, and to Africa and Asia, with a strong British tradition still present in Australia.

When we trace the original development of empirical political science, we can see that in a large number of European and American countries, political science is the result of empirical developments in public law. Consequently, the first difference concerns the difference between the perspective of law, which deals with “what ought to be”—with norms and the institutions that seek to embody them, and that of political science as transformed by behavioralism into an empirical social science, which is focused on “what is”—on the reality and on the explanations of it.

In Europe as well as in North and South America, there are other strong traditions that make contemporary history a parent of the new, post–World War II empirical political science. Here, despite all its ambiguities, the criterion of differentiation is between historical idiographic research, focused on the analysis of specific unique events, and a political science characterized by epistemological and methodological assumptions of other social sciences such as economics, sociology, and psychology, at least in terms of expectations of empirical findings (nomothetic) with a more general scope (regularities, patterns, laws). Social history and historical sociology as in the works of Reinhard Bendix, Barrington Moore, Stein Rokkan, Charles Tilly, and others have also greatly contributed to our understanding of long-term political processes at the macro-level. In this respect historical studies and political analysis can nicely supplement each other, as in the adage “Political science without history has no root, history without political science bears no fruit.”

Within the European and North American traditions, sociology is the third parent of the new empirical science. Here, in addition to the common epistemology and possibly methodology of research, the overlapping of the contents, when political sociology is considered, makes the differentiation more difficult. Such a criterion was set up by two famous sociologists of the 1950s, Bendix and Seymour Lipset, when they stated that political science starts from the state and analyzes how it influences society, whereas political sociology starts from the society and analyzes how it influences the state (Bendix & Lipset, 1957, p. 87). In other words, the independent variables of a sociologist are the dependent variables of a political scientist: The arrows of explanation are going in opposite directions. Such a distinction sounds artificial and unrealistic when the inner logic of research is taken into account—if we decide in advance what is/are the independent variable/s, how can we stop when no salient results come out and declare that from now on one becomes a sociologist or economist or else? Nevertheless, for years such a distinction was the rule of thumb used to stress the difference between political sociology and political science. However, such a rule was responding more to the necessities of differentiation between academic communities than to the needs of developments in empirical research. It must also be noted that political sociology can be understood in both a broad and a narrow sense. In the former, it covers the broad social-structural and political-cultural bases of politics and their long-term developments over time at the macro level. In the latter, the intermediate and input structures of politics like interest groups, parties, social movements and other aspects of civil society are dealt with. These, undoubtedly, belong more to the realm of political science proper and have continued to flourish. In the former sense, closer to historical sociology, a certain slackening can be observed. This is due to the fact that the consideration of long-term social-structural developments had rigidified to some extent in the 1970s and 1980s in variants of orthodox Marxism, or the political element had largely disappeared in the analysis of finer social distinctions in Pierre Bourdieu’s sense.

Last but not least, the development of differences between political philosophy and political science should be recalled. Again, there is much overlapping of contents, but epistemology and methods are different and easy to distinguish. As recalled by Giovanni Sartori (1984) with regard to the “language watershed,” first of all, the language is different: The words and the related empirical concepts of political science are operationalized, that is, translated into indicators and, when possible, in measures, whereas the language of political philosophy is not necessarily so; it usually adopts meta-observed concepts, that is, concepts that are not empirically translated.

As discussed in the next section, this apparently simple differentiation covers possible commonalities, but leaves unsolved how the two different disciplinary perspectives deal with normative issues. Norberto Bobbio (1971, pp. 367, 370) made a relevant contribution in this direction when he emphasized that political philosophy focuses mainly on

- the search for the best government;

- the search for the foundations of the state or the justification of political obligations;

- the search for the ‘nature’ of politics or of ‘politicness’; and

- the analysis of political language.

All four topics have an ethical, normative content, which is a characterizing feature of each political philosophical activity. At the same time, Bobbio recalls that an empirical analysis of political phenomena that are the objects of political science should satisfy three conditions:

- the principle of empirical control as the main criterion of validity;

- explanation as the main goal; and

- Wertfreiheit, or freedom from values, as the main virtue of a political scientist.

As noted in the discussion of epistemology above, the key element is in differentiating the speculative, ethically bound activity of a philosopher from the empirical analysis, even of phenomena that are influenced by the values of the actors.

The Influences of Other Disciplines

The obvious conclusion of the previous subsection is that there are different ways of analyzing political phenomena that correspond to different traditions and come from different cultural influences. Moreover, the discussion of those differences may help in developing a negative identity of political science. This is the very first meaning of the actual pluralism we have in this domain of knowledge: Pluralism only means that politics can be legitimately studied in different ways and with different goals that belong, at least, also to law, history, sociology, and economics. Pluralism in this sense challenges the autonomy of political science and even, in a radical version, has led to a denial that it constitutes a specific science. This view, however, no longer corresponds to the internal differentiation of the discipline, its specific achievements, and its more general institutionalization as an academic field. In addition, a second sort of pluralism inside political science proper reveals the overlapping and the influences of other disciplines in empirical political science. In this vein, when again considering the period starting after World War II, a main hypothesis can be proposed: Political science is influenced by the discipline or the other social science that in the immediately previous years has developed new salient knowledge. This is so for sociology, as can be seen in the analysis of Lipset and Bendix and other important authors since the end of World War II, who developed the work of classic sociologists, from Weber and Durkheim to Parsons and others. This is so for the influence of general systems theory, coming from cybernetics, and translated meaningfully into the analysis of political systems so that since the mid-1950s, it has become a major approach in political science. The same applies to the influence of functionalism, born with the developments of anthropology, and to rational choice or more specifically game theory, coming from economics and becoming more and more influential with several adaptations since the end of the 1950s. This is so, finally, for cognitive psychology that became very important in economics and at the same time in political science with the development of new ways of studying electoral behavior.

Moreover, when we consider more closely some of the subsectors of political science we can see more specific influences. For example, in the field of international relations, we can see the influence of international law. The public policies sector of political science has been influenced by sociology, economics, and constitutional and administrative law. Sociology has shaped the development of research on political communication. The influence of history can be seen in the selection of specific topics in comparative politics. Thus, we see that political science not only embodies a highly developed pluralism of the two kinds mentioned above, but also requires the integration of knowledge from other disciplines. Political scientists therefore also need an educational background that enables them to draw on these interdisciplinary sources of the field.

Recent Developments and Perspectives in Political Science

As the International Political Science Association notes on its website,

it is hard today for political scientists of 2011 to imagine the very different status their discipline in the world under reconstruction of 1949. In place of the familiar, well-structured web of national associations we know today, there were associations only in the United States (founded in 1903), Canada (1913), Finland (1935), India (1938), China (1932), and Japan (1948). (http://www.ipsa.org/history/prologue)

Founders of the International Political Science Association met in 1948 to plan for a new international organization that would establish dialogue among political scientists throughout the world. Taking into account the views of political science as variously defined in different countries, they identified four fields as constituting the discipline, acknowledging “the influence of the philosophers with ‘political theory,’ the jurists with ‘government,’ the internationalists with ‘international relations,’ and the fledgling behaviorist school of American political science with ‘parties, groups and political opinion.’” Today IPSA serves as the primary international organization in the field, with individual and institutional members as well as affiliations with national political science memberships across the globe.

With respect to the ways that pluralism and interdisciplinary developments have taken place in political science, the North American influence has been paramount. The so-called Americanization affected all of Europe as well as other areas of the world where native scholars, educated in North American universities, went back to conduct research and to teach, bringing a new empirical conception of the discipline that significantly contributed to create new communities of political scientists (Favre, 1985). Moreover, American foundations and research centers gave support for research in Europe, Latin America, Asia, and Africa. While there are differences in political science as it exists today on different continents in this domain of knowledge—and actually also in most other scientific research domains—the North American universities, as well as the American research centers and the scholars associated with them, had a great influence that can be compared only to the intellectual German influence during the 50 years between the end of the 19th century and the first 3 decades of the 20th century. Thus, at the end of the 1960s, Mackenzie (1969, p. 59) suggested that in this period 90% of political scientists worked in North America, and Klaus von Beyme noted that the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley had more professors in this field than all German universities combined. Moreover, in those years and earlier in the 1950s in all European countries and in Japan, the American influence had been very strong in all social sciences, with some exceptions such as anthropology, which had a specific French presence. Forty years later, 70% of all political scientists are almost equally present in North America and Western Europe and the other 30% are spread throughout the rest of world, again with a relatively strong presence in Japan.

To better understand the development of the discipline all over the world with its specific contents, approaches, and methods, we should note that the American influence has been supplemented by the great increase of faculty members in all universities of the world since the 1960s. During this period, especially in Europe, there was the so-called transition from elite universities to mass universities; that is, there was a significant growth in the number of university students, which required the recruitment of a large number of new faculty members in all disciplines, political science included. This growth of the discipline allowed the creation of academic groups who absorbed and translated the American influence in different ways. Without that internal growth, there would not have been even the possibility of such a widespread influence.

This penetrating influence had a different impact in the various countries also in connection with their respective traditions. More precisely, on the one hand, the influence of the way empirical research is developed through quantitative statistical analysis and qualitative research is general and fairly homogeneously widespread; on the other hand, some approaches that have a stronger correspondence or congruence in the European and Japanese traditions, such as the different neo-institutionalist approaches, have had more success than other approaches, such as the rational choice approach. That latter has become very strong in North American political science, where it has its roots in economics, but it has remained much weaker among political scientists in other areas of the world. By its very nature, political science in other regions of the world also has been more specifically historical and comparative rather than just focusing (mostly) on a single case, the United States. Moreover, the legal traditions of several European countries especially influenced research in the subfield of public policies. At the same time, traditions in political philosophy and contemporary history maintained some influence on research that was predominantly qualitative rather than quantitative. Finally, and more specifically in Europe, research funding from the European Union led to the development of a number of works focused on topics related to the Union.

In the most recent developments, the impact of a more continuous and effective communication among scholars through different modalities, such as domestic and international collective associations, research networks, and initiatives of private and public institutions, affected the discipline as a whole mainly in three directions. The first one is a growing trend toward blurring national differences and a consequent convergence between North America, or between North and South America, and Europe. The second is an increased blurring of subdisciplinary divides. This is so especially between comparative politics and international relations, traditionally two separate fields in the past. Such a trend is particularly evident in the European studies. Third, research in political science more and more focuses on relevant, contemporary realities rather than confining itself to an ivory tower, which made it distant and largely irrelevant and, consequently, created that “tragedy of political science” Ricci singled out years ago (1987). Contemporary political science thus has developed into a multi-faceted, well-established discipline that is concerned with the pressing problems of our times and provides sound empirical analyses and meaningful orientation in the ever more integrated and complex world of the 21st century.

References:

- Adorno, T., Albert, H. Dahrendorf, R., Habermas, J., Pilot, H., & Popper, K. R. (Eds.). (1969). Der Positivismusstreit in der deutschen Soziologie [The positivism debate in German sociology]. Darmstadt, Germany: Luchterhand.

- Almond, G. A., & Genco, S. (1977). Clouds, clocks, and the study of politics. World Politics, 29(4), 489–522.

- (1962). Politics. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. (Original work 350 BC)

- Bendix, R., & Lipset, S. M. (1957). Political sociology: An essay and bibliography. Current Sociology, 2(VI):79–99.

- Bobbio, N. (1971). Considerazioni sulla filosofia politica [Considerations on Political Philosophy]. Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica, 1(2), 367–380.

- Brady, H. E., & Collier, D. (2004). Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Clastres, P. (1975). La société contre l’Etat. [Society against the state]. Paris: Minuit.

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- D’Andrade, R. G. (1995). The development of cognitive anthropology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dahrendorf, R. (1977). Homo Sociologicus. Opladen, Germany: Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Deutsch, K. W. (1963). The nerves of government. New York: Free Press.

- Durkheim, É. (1975). Textes. Paris: Editions de Minuit.

- Easton, D. (1965). A systems analysis of political life. New York: Wiley.

- Easton, D., Gunnell, J. G., & Graziano, L. (Eds.). (1991). The development of political science. London: Routledge.

- Esser, H. (1993). Soziologie. Allgemeine Grundlagen [Sociology. General Foundations]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Campus.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. (1940). The Nuer. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Favre, P. (1985). Histoire de la science politique [History of political science]. In M. Grawitz & J. Leca (Eds.), Traité de science politique [Treatise of political science] (Vol. 1, pp. 28–41). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Foucault, M. (1970). The order of things. London: Routledge.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

- Goodin, R. E., & Tilly, C. (Eds.). (2006). Contextual political analysis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Habermas, J. (1975). Legitimation crisis. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Habermas, J. (1981). Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns [Theory of Communicative Action] (2 vols.). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

- Hempel, C. G. (1965). Aspects of scientific explanation and other essays in the philosophy of science. New York: Free Press.

- Jackson, R. (2000). The global covenant. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Kant, I. (1956). Kritik der reinen Vernuft [Critique of pure reason]. Hamburg, Germany: Felix Meiner. (Original work published 1787)

- King, G., Keohane, R. O., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing social inquiry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lasswell, H., & Kaplan, A. (1950). Power and societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lorenzen, P. (1978). Theorie der technischen und politischen Vernunft [Theory of technical and political reason]. Stuttgart, Germany: Reclam.

- Luhmann, N. (1984). Soziale Systeme [Social systems]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

- Lukács, G. (1967). Geschichte und Klassenbewußtsein [History and class consciousness]. Darmstadt, Germany: Luchterhand.

- Mackenzie, W. M. (1969). Politics and social science. London: Penguin.

- Madan, T. N. (Ed.). (1992). Religion in India. Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.

- Mbiti, J. S. (1969). African religions and philosophy. London: Heinemann.

- Merton, R. K. (1968). Social theory and social structures. New York: Free Press.

- Monroe, K. R. (Ed.). ( 2005). Perestroika! The raucous rebellion in political science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Morgenthau, H. (1948). Politics among nations. New York: Knopf.

- Moses, J. W., & Knutsen, T. L. (2007). Ways of knowing: Competing methodologies and methods in social and political research. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- (1945). The republic. New York: Oxford University Press. (Original work 360 BC)

- Popper, K. (1972). Objektive Erkenntnis. Ein evolutionärer Entwurf [Objective knowledge: An evolutionary approach]. Hamburg, Germany: Hoffmann und Campe.

- Quermonne, J.-L. (Ed.). (1996). Political science in Europe: Education, co-operation, prospects, report on the state of the discipline in Europe. Paris: Institut d’Etudes Politiques.

- Ricci, D. (1987). The tragedy of political science: Politics, scholarship, and democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Sartori, G. (Ed.). (1984). Social science concepts: A systematic analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Shin, D. C. (1999). Mass politics and culture in democratizing Korea. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Weber, M. (1968). Economy and society. New York: Bedminster.