Political repression continues to be a harsh reality in many states today. A large body of empirical political science literature seeks to understand why states imprison, torture, force disappearance of, or kill their own citizens. The empirical literature has demonstrated that several factors are associated with decrease in political repression; the most significant being domestic threat, especially civil war. Other factors are associated with increased repression; the most consistent being the level of democratization achieved within the state. The research suggests that commitment to rights through treaties and constitutional provisions, especially in tandem with an independent judiciary, may be one potential path to lessen repression, as is the role of international NGOs in the state.

Outline

- Introduction

- Measuring Political Repression

- Dominant Theoretical Approaches to Political Repression

- Empirical Findings

- Standard Model

- Democracy

- Domestic and External Threats

- Domestic Legal Commitments and Institutions

- International Treaties, Norms, and INGOs

- Bilateral, Multilateral, and Global Economic Influences

- The Future of Empirical Study of Political Repression

- References

Introduction

Political repression by one’s own state continues to affect almost half of the global set of countries today. For example, citizens in almost 60 countries live in a state with extensive political imprisonment, unlimited detention, and extrajudicial executions or other political murders and brutality. In more than 30 other countries, political murders and disappearances are a common part of life and may affect even those who are not politically engaged. Over the last two decades social scientists have produced a growing body of studies that systematically and rigorously examine theoretically important factors that may explain why states politically repress their own citizens. The empirical study of political repression focuses on two categories of state abuse of human rights and typically involves the creation and dissemination of large cross-national datasets that encompass the global set of countries and increasingly longer periods of time. Political repression is broadly defined as “involving the actual or threatened use of physical sanctions against an individual or organization, within the territorial jurisdiction of the state, for the purpose of imposing a cost on the target as well as deterring specific activities and/or beliefs perceived to be challenging to government personnel, practices or institutions” (Davenport, 2007b: 2). Most of the literature focuses on one of two forms of political repression separately – either addressing the more severe form of repressions, namely violations of personal or physical integrity (imprisonment, torture, killing, and disappearances) (e.g., Poe and Tate, 1994; Poe et al., 1999) or addressing the broader category of civil liberties restrictions that are typically of less severe form (e.g., Davenport, 1995). While the theoretical perspectives on the two forms of repression are largely indistinguishable, the most comprehensive examination of both categories of repression shows that while they are similarly influenced by the same agentic and structural factors, significant differences emerge with regard to the influence of domestic and external threats, an independent judiciary and constitutional provisions (Keith, 2012). Henderson (2004) makes an important contribution in expanding the traditional conceptualization and measurement of political repression to forms that are specifically targeted at females, which includes such acts as harassment, degrading treatment, denial of sanitary devices for women’s hygiene, virginity examinations, hostage taking to pressure male family members, imprisonment with men, absence of female guards, threats of rape, actual rape, forced prostitution, and pregnancy.

Measuring Political Repression

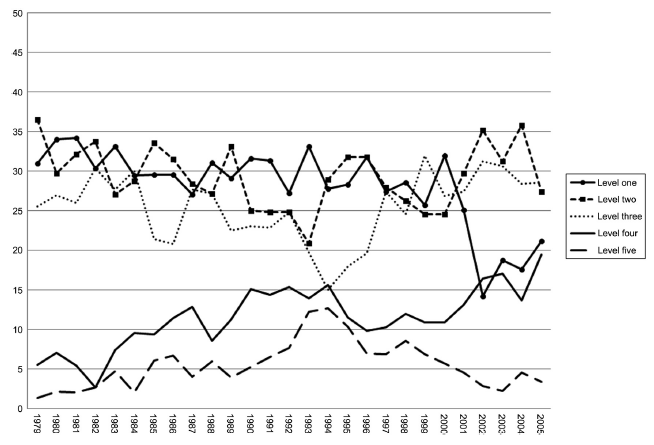

Social scientists seeking to empirically measure state repression face significant measurement issues, but over time political scientists have developed several measures that capture the level, frequency, and type of political repression. Most empirical studies to date have primarily addressed the most severe form of repression – violations of personal integrity (e.g., Poe and Tate, 1994; Poe et al., 1999; Cingranelli and Richards, 1999; Keith, 2002a) – and have tended to employ the dominant indicators in the field, for example, the Political Terror Scale (PTS) which is maintained by Gibney et al. (2014) (www.politicalterrorscale.org/) and is a standards-based measure of state use of political imprisonment, torture, killing, and disappearances that is operationalized as a five-point ordinal scale that ranges from one, where repression is rare, to five where repression is extensive and threatens the entire population. Figure 1 shows the percentage of countries at each level of political repression over time. We see a significant proportion of states achieving a score of one, the lowest level of repression or no repression, which ranges from 25 to almost 35%, with a significant drop following 2001. The proportion of countries with the highest level of repression (five) represents the smallest segment of countries, ranging from 2 to 12.5%. Level four of repression represents the second smallest segment here. We see the mid-levels of repression (two and three) affect approximately the same percentage of states over time as the lowest level of repression, with some variation over time. With the addition of a new measure, the CIRI physical integrity measure, which is maintained by Cingranelli et al. (2013), empirical studies can now examine the same four behavioral components individually or as an additive index. Some limitations and benefits adhere to each of these measures (see http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/Data/); most scholars deal with the trade-offs by conducting parallel analyses employing both measures. Conrad and Moore’s (2014) new Ill-Treatment and Torture (ITT) measures, while focusing on a single dimension of repression of personal integrity rights (torture), offers significant advantages over both the CIRI and PTS measures, in which it includes indicators related to the agents of torture, the victim type, and the level of torture (http://faculty.ucmerced.edu/cconrad2/Academic/ITT_Data_Collection.html).

Figure 1 Political repression of Personal Integrity Rights, 1979–2005.

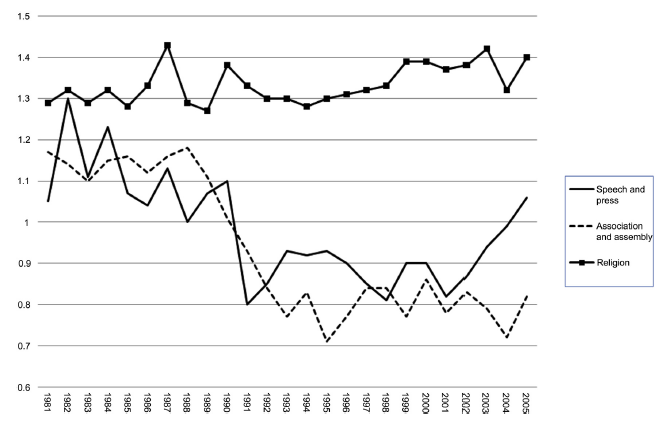

Measuring the level of state restrictions on civil liberties has proven to be more difficult. The two earliest popular measurements of political repression, Taylor and Jodice’s (1983) state coercive behavior and Freedom House’s civil liberties index (https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2014), represent significant data collection efforts, but each of them has significant limitations. Taylor and Jodice’s measurements are events counts that are limited in country and time coverage. The construction of the Freedom House’s civil liberties measure is unclear and the two of its four core components are problematic in that they do not specifically examine civil liberties protection per se, but rather measure circumstances and institutions that may facilitate or hinder the protection of civil liberties or deal with the abuse of these rights which would appropriately be classified as oppression of social and economic privileges falling outside the definition of repression above. Scholars now have access to new standards-based measures within the CIRI data project mentioned above that allow them to examine separately some core individual liberties such as freedom of religion, speech and press, and assembly and association. While the range of civil liberties they cover is limited and the pairing of rights is not theoretically intuitive, the measures do not suffer from many of the shortcomings of the Freedom House measure. Figure 2 presents the mean repression scores for CIRI’s freedom of speech and press, freedom of assembly and association, and freedom of religion measures. As with most studies, I have inverted the CIRI measures here to reflect repression of these freedoms, thus each of the three measures is now a three-point scale that ranges from zero to two with zero representing no repression and two the highest level of repression. We see several interesting trends. First, the most obvious pattern is that repression of religious freedom is consistently higher than repression of the other two sets of freedoms, and while there is some variation over time, there is virtually no improvement in the entire time period. Indeed, in 2005 we see a higher mean of repression than the beginning date of 1981. Second, we see a clear improvement in the level of repression for the other two categories of freedom, beginning with the end of the Cold War and leveling off in the mid-1990s with an increase in repression of speech/press beginning in after 2001, which could be related to the shift in emphasis to national security priorities following September 11. We do not see the same pattern, however, for freedom of assembly and association, which during most years is repressed less than speech and press freedoms.

Figure 2 Mean repression of freedom of speech and press, freedom of association and assembly, and freedom of religion.

Dominant Theoretical Approaches to Political Repression

Most of the current empirical work on political repression has approached the state’s behavior from the perspective of international relations theory, primarily utilizing a ‘soft’ rational choice perspective (e.g., Poe et al., 1999; and Davenport, 2007a) that assumes that political leaders are rational actors and that they choose from a menu of repressive tools because they perceive these tools to be the most effective means to achieve their chief end, which is to stay in power. The most pervasive factor that increases leaders’ willingness to employ the tools of repression is a threat to their rule, whether real or perceived, and that typically the more serious the perceived threat, the more willing state leaders are to employ repression (Keith and Poe, 2004; Keith, 2012). Or more broadly, as Davenport argues, state actors utilize actual or threatened physical sanctions in order to impose “a cost on the target as well as deterring specific activities and/or beliefs perceived to be challenging to government personnel, practices or institutions”; however, state actors carefully weigh the costs and benefits of engaging in repressive action, and also consider a menu of alternative mechanisms of control, as well assessing the odds of achieving their goals with these tools (2007a: 2–4).

The repression literature has drawn upon the theoretical insights of the domestic institutions/democratic peace perspectives – another stream within the rational actor approach. However, these perspectives dismiss the assumption of a unitary state actor and instead recognize the role of numerous domestic actors and institutions within the state (particularly in democratic regimes) which may affect the regime’s menu of acceptable policy options and/or the regimes’ calculation of costs and benefits related to commitment to international and national human rights norms and with subsequent (non)compliance to formal commitment to the norms. Poe et al. (1999) argue that state leaders in democratic regimes have less opportunity and less willingness to employ the tools of repression, even when facing domestic or international conflict or threats (293, and citations within). Opportunity is constrained because the structure and limited nature of democratic governments, which may include separation of powers and/or checks and balances, make it difficult for state actors to coordinate extensive use of repression. The necessity to utilize repression as a tool to solve conflict can be mitigated in democracies because they provide a variety of alternative mechanisms through which conflict can be channeled for possible resolution (Poe et al., 1999; Davenport, 2007b), in turn, weakening the state’s justification for coercive state action. In addition, the need to employ the tools of repression is also dampened by “the socialization processes that guide citizens of democratic polities toward the belief that nonviolent means of resolving conflicts are preferred over violence” (Poe et al., 1999: 293). The democratic norms of compromise, toleration, and facilitation may influence the decisions of the rulers by “increasing the cost of human rights violations as well as decreasing the value to quiescence” (Davenport, 1999: 96). The cost of repression is increased in democracy as the electoral process “provides citizens (at least those with political resources) the tools to oust potentially abusive leaders from office before they are able to become a serious threat” (Poe and Tate, 1994: 855). From the domestic legal institutions perspective it is not just democratic electoral processes, but also the legal institutions associated with democratic systems that can provide the public and other political actors the tools and venues through which they can hold the regime accountable, should it fail to keep its formal commitments, both domestic (Keith, 2002: 2012) and international (e.g., Powell and Staton, 2009). A truly independent judiciary, in particular, “should be able to withstand incursions upon rights because (1) the courts’ power and fiscal well-being are protected, (2) the courts have some ability to review the actions of other agencies of government, and (3) the judges’ jobs are constitutionally protected” (Keith et al., 2009: 649). Powell and Staton (2009) posit that in states where the courts are influential (effective), the use of repression may lead to rights claims in which the regime will incur a loss of resources as punishment for violating its obligations (154).

Another set of theoretical approaches generally focuses on transnational or international interaction and socialization which is believed to drive the creation of and commitment to international human rights norms, rather than rationalist calculations. These perspectives emphasize the transformative power of international normative discourse on human rights and the role of activism by transnational actors (international organizations and nongovernmental actors) who through repeated interactions with state actors induce states to accept new norms and also support local efforts to press for human rights commitment. Thus, their emphasis is on the processes through which state actors adopt formal constraints on the state’s opportunity to repress and through which state actors eventually internalize international human rights norms or values which over time removes many of the tools of repression from the state’s menu of appropriate policy options. The transnational advocacy networks posits that international human rights norms are diffused through networks of transnational and domestic actors who “bring pressure ‘from above’ and ‘from below’ to accomplish human rights change” (Risse and Sikkink, 1999: 18). A second perspective, the world society approach (e.g., Meyer et al., 1997) perceives states to be embedded in an integrated cultural system that “promulgates cognitive frames and normative prescriptions that constitute the legitimate identities, structures, and purposes of modern nation-states” (Cole, 2005: 477). Thus, with the proliferation of human rights treaties codifying human rights norms, states’ legitimacy, or ‘good nation’ identity is increasingly linked to the formal acknowledgment of these norms and newly emerging or independent states will be likely to adopt standardized forms of government (Go, 2003). However, as Cole notes, many states join the traditionally weak human rights regime, “not out of deep commitment, but because it signals their probity to the international community” and thus “a decoupling is endemic to the human rights regime” (p. 477).

Empirical Findings

Standard Model

While much of the early repression work was quite thin in terms of applying broad theoretical approaches, as Davenport and Armstrong (2004) note, over time a ‘standard’ model has emerged in the repression literature (Poe and Tate, 1994; Poe et al., 1999 and the numerous citations within) that includes nine variables: level of democratization, which is discussed separately in the following sections; two forms of threat (civil war and international war), which are also discussed in the following sections; two additional regime types (military and leftist regimes); and socio-economic conditions (economic development, population size, and colonial legacy). All of but one of the variables within the model represent the domestic environment of the state that either constrains or creates the regime’s opportunities to repress or that affects the regime’s decision-making calculation of the advantage or disadvantage to exercising repressive tools as a means to achieve its policy goals. Over time the body of empirical work has expanded beyond domestic influences to examine a variety of international or transnational influences, including bilateral aid, multilateral lending programs, international treaty regimes, trade relations, and foreign investments. As the models of repression have expanded, the latter five variables of the standard model above have performed inconsistently. And while they continue to be used as control variables, other variables have become more theoretically and statistically important.

Democracy

Democracy is the most widely tested and consistently performing variable in the standard model. While the literature has tended to assume a linear association between the level of democracy and repression, recent theoretical and empirical work suggests that this oft unstated assumption does not accurately reflect the true relationship between democracy and repression. In more recent work, Davenport and Armstrong (2004) as well as Bueno de Mesquita et al. (2005) argue and demonstrate empirically that the relationship between democracy and repression has been misspecified and that a threshold effect is a more accurate characterization. Other scholars have perceived democracy as a multidimensional concept and have found that some dimensions of democracy are more likely to lessen the use of political repression – most particularly, the competitiveness of political participation (Keith, 2002a; Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2005).

Domestic and External Threats

Theoretically, the most significant factor is the presence of domestic opposition or a perceived challenge to the regime’s hold on power, especially if there is a threat (actual or perceived) that the regime’s challengers may resort to violent tactics. The regime may choose to employ coercive force to prevent, contain, or punish such threats. The most potentially disruptive form of domestic threat, civil war, has received the most empirical attention, and its effect has been demonstrated to be the strongest of many factors, in terms of impact, statistical robustness, and consistency across a variety of measures of repression and other human rights behavior. To illustrate the magnitude of its impact, Poe et al. (1999) demonstrate that an ongoing civil war would increase the level of repression over time by around one and half points on a five-point scale of repression, with other factors in the model held equal (p. 308). The literature has also sought to understand the impact of less severe forms of threat, as well as other dimensions of threat, such as the variety of strategies and frequency of conflict. For example, Davenport (1995) found that deviance from past norms of conflict, the frequency of conflict, and the variety of strategies engaged, each increase the likelihood that a state would resort to civil liberties restrictions; however, once these factors are controlled the presence of domestic violence becomes statistically insignificant. Poe, Tate, Keith, and Lanier (2000) found that the repressive response to domestic threats was dependent not only on the level of the threat but also upon the prior level of repression. Regan and Henderson (2002) also found that the level of threat was positively associated with repression, and that the impact of threat was greater than that of regime type. External threats are also theoretically important, and the empirical literature has consistently confirmed the effect of international war participation on domestic political repression, and thus over time, international war has become a key component of the standard model of human rights behavior (Poe and Tate, 1994; Poe et al., 1999; Cingranelli and Richards, 1999; Davenport and Armstrong, 2004); however, the impact of international war is substantially lower than that of civil wars. For example, Poe et al. 1999 found the impact of participation in a civil war to be at least three times the impact of being a participant in an international war. This is somewhat intuitive even though external threats such as interstate war are potentially more serious than civil wars, often civil wars are a greater threat to regime due to the proximity and ability of the opposition to impose damage, especially compared to some interstate wars, which may be fought far away from at least some of the belligerents’ states, such as in the Persian Gulf War or the War in Iraq.

Domestic Legal Commitments and Institutions

A growing body of research has examined the question of whether constitutional provisions for rights and an independent judiciary constrain the likelihood of states repressing their own citizens. Most of these studies have examined the role of specific rights, typically imbedded bills of rights (e.g., Davenport, 1996; Keith, 2002a; Keith et al., 2009; Keith, 2012) and to a lesser extent have examined institutional constraints such as provisions for an independent judiciary (Blasi and Cingranelli, 1996; Keith, 2002b; Keith, 2012), states of emergency clauses (Keith and Poe, 2004; Keith, 2012), or provisions for federalism (Blasi and Cingranelli, 1996). Most of the earliest analyses found evidence that not only were the constitutional rights provisions not associated with improved rights behavior, the associations were in the opposite direction, suggesting a harmful effect. As studies have improved in their temporal and spatial dimensions and have become more sophisticated methodologically, the observed effect of constitutional rights provisions has become somewhat more consistent and suggests a beneficial effect overall. The effect of constitutional provisions for judicial independence appears to be more appropriately conceptualized as influencing de facto judicial independence, which in turn consistently decreasing the probability of repression of all forms (Keith, 2012). One set of constitutional provisions remains problematic – studies have consistently argued and demonstrated that certain provisions for states of emergencies (such as derogation clauses), which have been promoted by international organizations such as the International Lawyers Association and International Commission of Jurists, have unintended consequences and are largely associated with increased levels of repression.

International Treaties, Norms, and INGOs

Measuring norms is probably the most difficult task that empiricists face in testing normative approaches, and thus most empirical studies of compliance have examined surrogate indicators. Following Goodliffe and Hawkins’ (2006) work on treaty commitment, Keith et al. (2009) use regional and global commitment rates to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) as measures of norms, but find no effect in a variety of models of repression. Powell and Staton (2009) test regional and global norms, as indicated by past rates of torture, in their Convention Against Torture (CAT) models; however, they find too little evidence that norms influence state torture practices. Most empirical studies of state compliance with international human rights treaty obligations focus on the state’s provision or protection of the guaranteed rights embedded in the document. The bulk of the empirical compliance literature, while grounded in rich theoretical debate concerning the influence of human rights treaties, has largely been limited to tests of whether being a state party produces a positive or negative effect, controlling for a variety of factors. It does not enable us to determine which of the mechanisms that are hypothesized to be at work are actually operative. While the literature examines a broad range of human rights behavior, much of the research has focused on rights abuse that would appropriately be labeled as political repression. Extant empirical evidence of influence of participation in the international human rights regime has been rather mixed. For example, Keith (1999) finds no effect from the ICCPR on either form of political repression, unless controlling for state derogations. Hathaway (2002) finds that most treaties within the human rights regime do not significantly affect human rights behavior, and that participation in some of the treaties, such as the CAT produce negative effects, a result which is confirmed by Hafner- Burton and Tsutsui (2005) in regard to a wide range of treaties. On the other hand, the most exhaustive compliance studies (Landman, 2005) found consistent evidence of an association between rights behavior and state commitment to a variety of treaties within international human rights regime. Landman finds that commitment to the ICCPR and the CAT, even while controlling for the level of reservations decreased state repression of personal integrity rights, torture, and civil and political rights. On the other hand, Hill’s (2010) sophisticated analysis of the CAT and the ICCPR, finds both to be associated with increased repression. Keith’s (2012) comprehensive analysis of both forms of political repression (and a variety of measures), found that the ICCPR has both a beneficial unconditional effect and an interactive effect with international NGOs (INGOs); however, the Optional Protocol to the treaty, only has an effect in conjunction with the presence of INGOs. The CAT has neither conditional nor unconditional effect on any form of repression, regardless of measures. Thus, our understanding of international treaties’ ability to reduce repression remains sketchy.

The presence of transnational networks or civil society pressure (typically measured as the number of INGOs in which citizens have membership) is much easier to measure than the presence of norms; however, the direct link between treaty ratification and civil society pressure is not typically tested in human rights models. Both Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui (2005) and Powell and Staton (2009) find that as the number of INGOs to which citizens belong increases, the level of protection of human rights increases. Neumayer (2005) provides the most rigorous analysis, examining specifically the effect of treaty commitment on human rights behavior, conditioned upon the strength of civil society organizations. However, his results are rather mixed: he does find that the stronger the state’s participation in INGOs the greater the beneficial effect of ratification of the CAT on human rights behavior; however, the results do not hold for ICCPR ratification. He also finds mixed results in regard to regional treaties. For example, while the benefit of ratification of the Inter-American torture convention increases as INGO participation increases, the effect does not hold for the European torture convention.

Overall, the observable effect of norm diffusion is rather weak and inconsistent at best. The evidence of a strong positive influence by NGOs on states human rights practices is more convincing; however, we must keep in mind that the civil society linkage through treaty ratification is not directly demonstrated except in Neumayer’s work. The evidence of the beneficial effect of treaty commitment continues to grow with more sophisticated and rigorous analyses, with the exception of the CAT, which has no observable benefit.

Bilateral, Multilateral, and Global Economic Influences

As the field has grown over time, increasing attention has focused on bilateral, multilateral, and global economic influences. While much attention has been given to impact of repression on bilateral aid allocation, relatively little attention has been given to the question of whether U.S. aid influences human rights practices of recipient states (e.g., Shoutlz, 1981; Regan, 1995; Apodaca, 2001) beyond the two studies supported by USAID itself (Finkel et al., 2006, 2008) and by Knack (2004), by a senior research economist for the World Bank who examined the impact of western foreign assistance on democratization in recipient states. While there are strong theoretical links between aid and improved human rights practices, both direct and indirect, there is also some justification to expect that aid would not influence human rights or that it might even have a harmful effect. Overall, the empirical evidence suggests that bilateral aid has limited (Regan, 1995; Apodaca, 2001) or no effect (Knack, 2004), and sometimes a harmful effect (Shoultz, 1981). Two comprehensive analyses of the USAID democracy and governance aid commissioned by the USAID itself have consistently demonstrated that while spending in the other subsectors of aid (elections, civil society, and governance) all produce the desired effects, spending on the human rights component of the rule of law program has a strong negative effect on states’ human rights protection, regardless of numerous controls, including controls for endogeneity, and regardless which measure of human rights is employed (Finkel et al., 2006, 2008). As the investigators note in the final report of their second study, their “effort to untangle the web of relationships that may underlie this distressing and presumptively anomalous relationships and to model them statistically has been largely unsuccessful in its basic purpose” (Finkel et al., 2008: 57). While scholars seem somewhat reluctant to expect these null or negative findings, we are left with the dilemma that aid may actually promote political repression, at least under some circumstances. Recent empirical studies of the influence of multilateral aid programs have been just as pessimistic. A growing number of empirical studies have demonstrated the IMF structural adjustment programs lead to increased repression. The most comprehensive and rigorous study to date (Abouharb and Cingranelli, 2008) demonstrates that the structural adjustment programs of both the IMF and World Bank increase civil conflict which in turn increases the state’s level of physical integrity. The evidence in regard to global economic influences, such as trade openness and foreign economic penetration is mixed but somewhat more optimistic than that of the aid relationship.

Empirical studies that have tested liberal economic theory on the link between trade and human rights protection, although small in number, have consistently confirmed these expectations (e.g., Apodaca, 2001; and Harrelson-Stephens and Calloway, 2003). The evidence examining the effect of foreign investment has been much more inconsistent, often dependent upon the category of repression with FDI reducing only the likelihood of political repression of civil liberties not the personal integrity (Apodaca, 2001; Richards et al., 2001). Keith’s (2012) more comprehensive study of a three-decade period consistently found that all indicators of global embeddedness (trade, FDI, and WTO membership) were associated with increased odds of both forms of repression. Overall, the effect of bilateral and multilateral aid, as well as those of global economic influences, proves consistently to be in a direction that is harmful to human rights, and to increase the likelihood of repression.

The Future of Empirical Study of Political Repression

Several limitations across the literature suggest the direction for future research. While the theoretical approaches that have informed the empirical examination of state repression has expanded to draw a wider range of disciplines, an integrative grand theory is yet to evolve. And while the reification of the state as a unitary actor has faded somewhat with the integration of the domestic institutions approaches, the empirical literature continues largely to ignore the individual, actual agents of the state (or private actors sanctioned by the state) who directly engage in the human rights violations. This lack is likely linked, in part, to severe data limitations that restrict the growth of the field. For this body of research to progress, social scientists must create data that move the temporal dimension of the data beyond the arbitrary calendar year. These finer delineations are necessary to capture the response of states to particular events, especially in terms of perceived threats to the regime. In addition, scholars need to follow the lead of Conrad and Moore and create variables that identify the state or state-sanctioned actors (and their relevant characteristics) who engage in or facilitate repression, and similarly, variables that identify the targets of repression. Finally, scholars should move toward capturing a more nuanced understanding of the modalities of repression, especially in regard to the variation in legality. This improvement would allow scholars to examine the substitutability of tools of repression.

References:

- Abouharb, R., Cingranelli, D., 2008. Human Rights and Structural Adjustment. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Apodaca, C., 2001. Global economic patterns and personal integrity rights after the cold war. International Studies Quarterly 45, 587–602.

- Blasi, G., Cingranelli, D., 1996. Do Constitutions and Institutions Help Protect Human Rights? In: Cingranelli, D. (Ed.), Human Rights and Developing Countries. JAI, Greenwich.

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., Downs, G., Smith, A., Cherif, F., 2005. Thinking inside the box: a closer look at democracy and human rights. International Studies Quarterly 49, 439–457.

- Cingranelli, D., Richards, D., 1999. Measuring the pattern, level, and sequence of government respect for human rights. International Studies Quarterly 43, 407–417.

- Cole, W., 2005. Sovereignty Relinquished? Explaining Commitment to the International Human Rights Covenants, 1966–1999. American Sociological Review 70, 472–495.

- Conrad, C., Moore, W., 2014. The Ill-Treatment and Torture Data Collection Project. http://faculty.ucmerced.edu/cconrad2/Academic/ITT_Data_Collection.html (accessed November 20, 2017).

- Davenport, C., 1995. Multi-Dimensional threat perception and state repression: an inquiry into why states apply negative sanctions. American Journal of Political Science 39, 683–713.

- Davenport, C., 1996. Constitutional promises’ and repressive reality: a cross-national time-series investigation of why political and civil liberties are suppressed. Journal of Politics 58, 627–654.

- Davenport, C., 1999. Human rights and the democratic proposition. Journal of Conflict Resolution 43, 92–116.

- Davenport, C., 2007a. State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Davenport, C., 2007b. State repression and political order. Annual Review of Political Science 10, 1–23.

- Davenport, C., Armstrong, D., 2004. Democracy and the violation of human rights: a statistical analysis from 1976 to 1996. American Journal of Political Science 48, 538–554.

- Finkel, S., Pérez-Liñán, A., Seligson, M., Azpuru, D., 2006. Effects of U.S. Foreign Assistance on Democracy Building: Results of a Cross-National Quantitative Study. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnade694.pdf (accessed November 20, 2017).

- Finkel, S., Pérez-Liñán, A., Seligson, M., Tate, N., 2008. Deepening Our Understanding of the Effects of US Foreign Assistance on Democracy Building Final Report. http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADL961.pdf (accessed November 20, 2017).

- Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R., Haschke, P., 2014. Political Terror Scale 1976– 2012. http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/ (accessed November 20, 2017).

- Go, J., 2003. A globalizing constitutionalism? views from the postcolony, 1945–2000. International Sociology 18, 71–95.

- Goodliffe, J., Hawkins, D., 2006. Explaining commitment: states and the convention against torture. The Journal of Politics 68, 358–371.

- Hafner-Burton, E., Tsutsui, K., 2005. Human rights in a globalizing world: the paradox of empty promises. American Journal of Sociology 110, 1373–1411.

- Harrelson-Stephens, J., Callaway, R., 2003. Does trade openness promote security rights in developing countries? examining the liberal perspective. International Organizations 29, 143–158.

- Hathaway, O., 2002. Do human rights treaties make a difference? Yale Law Journal 111, 1935–2042.

- Henderson, C., 2004. The political repression of women. Human Rights Quarterly 26, 1028–1049.

- Hill, D., 2010. Estimating the effects of human rights treaties on state behavior. The Journal of Politics 72, 1161–1174.

- Keith, L., 2002a. Constitutional provisions for individual human rights (1976–1996): are they more than mere “Window Dressing?”. Political Research Quarterly 55, 111–143.

- Keith, L., 2002b. International principles for formal judicial independence: trends in national constitutions and their impact (1976 to 1996). Judicature 85, 194–200.

- Keith, L., 2012. Political Repression: Courts and Law. University of Pennsylvania Press, Penn.

- Keith, L., Poe, S., 2004. Are constitutional state of emergency clauses effective? an empirical exploration. Human Rights Quarterly 26, 1071–1097.

- Keith, L., Tate, N., Poe, S., 2009. Is the law a mere parchment barrier to human rights abuse? Journal of Politics 71, 644–660.

- Knack, S., 2004. Does foreign aid promote democracy? International Studies Quarterly 48, 251–266.

- Landman, T., 2005. Protecting Human Rights: A Comparative Study. Georgetown University Press, Washington, DC.

- Meyer, J., Boli, J., Thomas, G., Ramirez, F., 1997. World Society and the Nation-State. American Journal of Sociology 103, 144–181.

- Poe, S., Tate, N., 1994. Repression of human rights to personal integrity in the 1980s: a global analysis. American Political Science Review 88, 853–872.

- Poe, S., Tate, N., Keith, L., 1999. Repression of human rights to personal integrity revisited: a global cross-national study covering the years 1976–1993. International Studies Quarterly 43, 291–313.

- Poe, S., Tate, N., Keith, L., Lanier, D., 2000. The continuity of suffering: domestic threat and human rights abuse across time. In: Davenport, C. (Ed.), Paths to State Repression: Human Rights and Contentious Politics in Comparative Perspective. Roman Littlefield, Boulder.

- Powell, E., Staton, J., 2009. Domestic judicial institutions and human rights treaty violation. International Studies Quarterly 53, 149–174.

- Regan, P., 1995. US economic aid and political repression: an empirical evaluation of US foreign policy. Political Research Quarterly 48, 613–628.

- Regan, P., Henderson, E., 2002. Democracy, threats, and political repression in developing countries: are democracies internally less violent? Third World Quarterly 23, 119–136.

- Richards, D., Gelleny, R., Sacko, D., 2001. Money with a mean streak? foreign economic penetration and government respect for human rights in developing countries. International Studies Quarterly 45, 219–239.

- Risse, T., Sikkink, K., 1999. The socialization of international human rights norms into domestic practices: introduction. In: Risse, T., et al. (Eds.), The Power of Human Rights: International Norms and Domestic Change. Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 1–38.

- Schoultz, L., 1981. Human Rights and United States Policy toward Latin America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

- Taylor, C., Jodice, D., 1983. World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators. Yale University Press, New Haven.