Public policy is a set of decisions by governments and other political actors to influence, change, or frame a problem or issue that has been recognized as in the political realm by policy makers and/or the wider public. Scientific approaches toward public policies have proliferated over the postwar period as the size and scope of government interventions have continuously expanded. In political science, the study of public policy includes policy analysis or policy science, which identifies effective policy measures, policy instruments, which a government can employ, and the policy process, which analyses how a government comes to take a decision.

Outline

- Introduction

- Origins of Public Policy

- Policy Analysis, Policy Science and Evidence-Based Policy Making

- Evidence-Based Policy Making

- Tools of Government

- Politics and Institutional Constraints

- Outlook

- References

Introduction

Public policy is a set of decisions made by governments and other political actors to influence, change, or frame a problem or issue that has been recognized as being in the political realm by policy makers and/or the wider public. Public policy can also take the form of a nondecision (Dye, 1972) or a deliberate neglect (Klein and Marmor, 2006). Strategic approaches toward public policies have proliferated over the postwar period, as the size and scope of government interventions have continuously expanded. Today, there are still high expectations about the problem-solving capacities of public policies, even though, in the last couple of decades, many policy problems could not be solved. Trust in government is also declining and problem solving has been increasingly taken up by private sector initiatives. These can be found in the form of social enterprises, charities, or business activities.

The study of public policy includes policy analysis or policy science, which identifies effective policy measures, policy instruments, which a government can employ, and the policy process, which analyses how a government comes to make a decision. The fundamental question in the study of public policy is still to reconcile the fundamentally different constraints in the field of politics and the field of policies. While many policies are now available for solving problems and policy knowledge is vastly improved, many policies remain politically contested.

Origins of Public Policy

Until the full democratization of modern societies set in, politics was the process of establishing order and power. Public policies were one part of politics as they were employed to satisfy certain political demands. They were usually part of the political process and not necessarily aimed at particular political goals in their own right or to solve problems. The German chancellor, Otto Bismarck, introduced social insurance to pacify the increasingly restless working class in Germany and to pre-empt sympathy for the fledgling social democrats. The underlying problem of social risks was hardly on policy makers’ minds until well into the twentieth century. Democratization, however, gave rise to higher expectations from the public with regard to governmental responsibility. The consequences of the Great Depression led to an increased study of policy tools as a way to stabilize national economies in an international context. The failure to find and implement an appropriate response to the underlying problems of the Great Depression, and the subsequent rise of fascist governments in Europe and Japan, followed by World War II, increased awareness about the need for more clearly designed and planned public policy for both political and economic stability in industrialized countries.

The postwar period, therefore, saw the development of more professional policy planning across the industrialized world and the rise of public policy as a function of governments. In the socialist Eastern bloc all economic and social activities by governments were based on complex planning procedures in state bureaucracies. A detailed command and control structure was applied to major spheres of life. In the Western world, education, health, social, and pension policies became important fields for public policies. But also industrial and economic policy, the labor market and defense were key activities of central governments. Today, public policies have now been developed for almost all issues and questions in modern societies, ranging from birth control and consumer protection to assisted suicide. There is hardly any aspect of modern living which is not touched upon by public policy. Governments have approaches and positions on virtually everything, with maybe the exception of fashion and cultural tastes. But even here major mass media outlets are in the public sector and shape the consumption of popular culture.

The process of expanding public policy to all parts of life was accompanied by a continuous increase of public spending as part of GDP in the industrialized world between WWII and the mid-1980s, as well as a massive expansion of legislative activities and regulation. This has not been reversed by trends toward privatization and deregulation since the 1980s as both generally require new rules and public supervision. Public spending is stagnating at a relatively high level and today’s economies cannot survive without active involvement by governments.

The initial enthusiasm for public policy as a problem-solving device has waned. Trust in governments to solve pressing problems is at an all-time low. The first two decades after WWII were full of hope that an orderly approach toward policies could eradicate the most serious problems in modern societies. Poverty, crime, drug abuse, low skills, and unemployment were seen as social problems which could be addressed and solved with public policies, if enough knowledge and research were applied to find the best solution. These hopes were dashed for several reasons: first, finding good and appropriate policies to address problems was more complex than initially thought. There is still no one decisive answer as to how to eliminate poverty or crime in open societies. Second, potential policy tools such as redistribution, public spending, social spending, and public work schemes are strongly politically contested in all modern democracies, even where they have been proven effective. The policies of the Nordic countries, which generally have higher levels of education and health and lower levels of crime and unemployment, have rarely exported these policies to other areas as they rely on historical political compromise as well as political institutions which were not in place elsewhere. Third, problem definitions were also subject to political contestation: do governments have to be concerned with consumption patterns of their citizens if it affects their health or wellbeing? Fourth, the size of government as well as its role remains a topic of debate. Fifth, policy effectiveness is only one criterion among many for policy makers and often not seen as the most important one. Some policies are not in line with general values or political preferences. Many studies have shown, for instance, that incarceration rarely prevents reoffending. Nevertheless, the value of punishment for offenders remains a strong reason for imprisonment. Finally, policies very often produce winners and losers and impact the political process (Lowi, 1971). Many insights in public health on healthy eating and exercise have not led to policies as they potentially have a negative impact on producers. For instance, the effects of meat and high levels of sugar and alcohol are well known but have not led to effective policies to curtail them. Banning sugar or even increasing information about sugar in food, meets fierce resistance from major manufacturers, and yet tobacco is under heavy attack by policy makers. In other words, the politics of policy making is still the main factor influencing public policies, not their problem-solving capacity.

Policy Analysis, Policy Science and Evidence-Based Policy Making

The academic field of public policy originated in the United States as a turn toward a scientific analysis of policies (rather than politics, as in the much older field of political science). The growth of government and the increasing expectation that governments were to solve specific public problems, such as unemployment, poverty or housing, led to the emergence of policy science as a new approach (Lasswell, 1951). Howard Lasswell suggested that better policy and better government could be achieved through the intelligent use of the social sciences. Just as no energy grid could work without the knowledge of engineers and monetary policy is based on the advice of economists, all parts of government should be organized in a way that independent scientific knowledge would lead the way toward better policy making. For maximizing the effects of policy science, research should focus on three aspects: to be multidisciplinary, problem solving, and normative (Deleon, 2006; Howlett et al., 2009).

In particular, the practical application of policy solutions for real-world problems was the driving force for setting up schools and research institutes dealing with public policy. Government bureaucracies themselves integrated policy sciences into their administrative structures during the 1960s. In the United States by the 1980s virtually every federal office had a policy branch (Deleon, 2006). They aimed to identify objective and scientific solutions for clearly defined policy problems. The task of the policy analyst was to apply the best available knowledge from all disciplines to a given problem in order to find the best available solution and to mediate between science and politics. Dunn defined policy analysis, for example, as an applied social science discipline that uses multiple research methods in a context of argumentation, public debate in order to create, critically evaluate and communicate policy-relevant knowledge (Dunn, 1994). Policy science increasingly built on existing knowledge to propose a policy solution. Eugene Bardach, at the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California Berkeley, published A Practical Guide for Policy Analysis: The Eightfold Path to More Effective Problem Solving. The book identifies in detail the steps toward successful policy analysis as follows: (1) define the problem; (2) assemble some evidence; (3) construct the alternatives; (4) select the criteria; (5) project the outcomes; (6) confront the trade-offs; (7) decide; and (8) tell your story. Steps (1)–(6) would be based on scientific research dealing with a policy problem. Only the last two steps would put the policy issue in a wider political context. The persuasion, argumentation and reasoning were an important part of policy science in addition to policy analysis which determined the best approach.

After an initial phase of enthusiasm for large-scale policy planning, such as the War on Poverty in the United States, or initiatives for economic planning in Europe, the 1970s and 1980s saw an increasing disillusionment with the power of scientifically based policies. Many policy suggestions were not taken up by policy makers and the implementation of policies was found to be harder than the policy designers had anticipated. Also many policy fields are complex and particular measures have a knock-on effect. Attempts to fix one problem create several more (Moran et al., 2006). Primarily in the field of economic policy, the recession during the 1970s triggered by oil-shocks demonstrated the limits of economic management and the fact that governments were not in control of the business cycle. Unemployment, poverty, and low educational attainment returned to the policy agenda. In many countries a new debate about the limits of the state and state responsibility emerged. Whereas previously governments aimed to alleviate social problems, they now seem to increasingly accept the nature of societies as unequal and imperfect.

Today, specialist research institutes and universities deal with specific policy concerns in great detail. Research in economics has advanced the understanding of different parts of the economy and influences public policy a great deal. Sociology, demography, public health, engineering, and environmental studies have also provided many policy suggestions to policy makers. Government bureaucracies issue policy research either by assessing potential outcomes of particular policies or evaluating existing policies. Microeconomic research models incite structures and frequently propose public policies to improve regulation, taxation, and spending.

Policy science today is based on a model of demand (by governments) and supply (by researchers) (Deleon, 2006). Rather than integrating research into government bureaucracies and establishing expanded research and planning units, as was foreseen in the 1960s, many governments rely on a host of university and institute-based research for individual policy problems. Independent research output competes for attention in the political arena and is occasionally used in either parliamentary hearings or government programs to improve policy design. The separation of governments and research institutions also allows for a greater plurality in methods and approaches, as well as political preferences. The hope by Laswell that each policy problem would have one best solution, which could be identified by applying the best knowledge, has been replaced by a market place for solutions that offers different pros and cons as well as different distributional outcomes. Expectations toward social engineering as well as economic management today are much more modest than in the early postwar period. Policy science as a science in itself has been in disarray as it could not establish and institutionalize one dominant approach toward problem solving (Klein and Marmor, 2006). At the same time, the role of scientific advice for policy makers has never been stronger.

Evidence-Based Policy Making

Recently a new form of policy science has emerged under the rubric of evidence-based policy making (Radaelli, 1995). Pioneered in medicine, where evidence of effectiveness is now a major criterion for developing guidance, the British government under Tony Blair engaged in further developing a science-based policy prescription. In the UK, evidence-based policy making was supported by grants from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) to the Evidence Network in 1999. The Evidence Network is a center for evidence-based policy and practice. At the core of evidence-based policy making is the systematic testing of the policy’s effectiveness. It includes the counterfactual and asks what would have happened without the policy change. Effects of a policy are measured both directly as well as indirectly. The decision in favor or against a policy is then taken in a cost–benefit perspective which aims to assess the net benefit of a policy change.

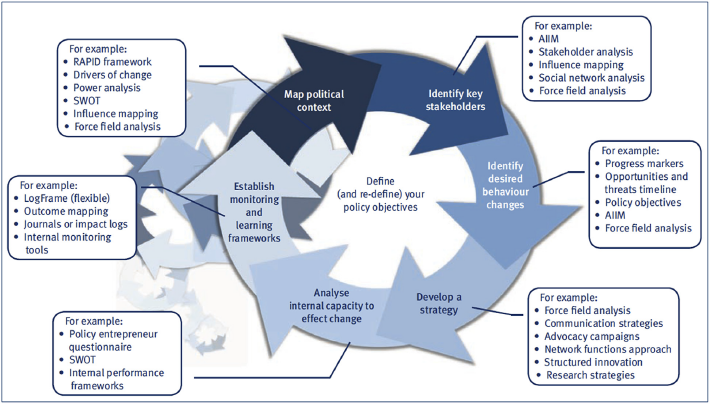

Evidence-based policy is used in development policy and has been advanced by the RAPID Outcome Mapping Approach (ROMA) through the British Overseas Development Institute (ODI). It is based on six key assumptions (Young and Mendizabal, 2009). They include first, that policy processes are complex and rarely linear or logical. Simply presenting information to policy makers and expecting them to act upon it is very unlikely to work. They are not purely linear as they have various stages that each take varying lengths of time to complete and may be conducted simultaneously. Strategies must be fluid. Second, many policy processes are only weakly informed by research-based evidence. Third, research-based evidence can contribute to policies that have a dramatic impact on lives. Fourth, policy entrepreneurs need a holistic understanding of the context in which they are working. While there are an infinite number of factors that affect how one does or does not influence policy, it is relatively easy to obtain enough information to make informed decisions on how to maximize the impact of research on policy and practice. Fifth, policy entrepreneurs need additional skills to influence policy. They need to be political fixers, able to understand the politics and identify the key players. Finally, policy entrepreneurs need clear intent – they need to really want to do it. Turning a researcher into a policy entrepreneur, or a research institute or department into a policy-focused think tank involves a fundamental reorientation toward policy engagement rather than academic achievement; engaging much more with the policy community; developing a research agenda focusing on policy issues rather than academic interests; acquiring new skills or building multidisciplinary teams; establishing new internal systems and incentives; spending much more on communications; producing a different range of outputs; and working more in partnerships and networks.

As the key lessons from evidence-based policy making show, understanding the relationship between research, policy and implementation is as complex as the older and more traditional policy science. To develop policy advice for policy makers is not easy or straightforward (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The RAPID outcome mapping approach (ROMA).

Reproduced from Young, J., Mendizabal, E., 2009. Helping Researchers Become Policy Entrepreneurs: How to Develop Engagement Strategies for Evidence-Based Policy-Making. Overseas Development Institute.

Tools of Government

Public policies come in many different forms and sizes as governments have a whole array of instruments at their disposal. Policy problems can be defined and solved in many different ways as the following example can illustrate. The pollution of a public space can be stopped by either convincing citizens not to drop their litter; by introducing a fine for littering; by supplying more bins or by giving firms subsidies for removing and recycling the litter. Depending on the approach chosen, very different groups of the public will be made responsible for solving the problem: the citizens through persuasion or coercion; the city council through the provision of bins or private business.

There are many categorizations and typologies of different tools (Dahl and Lindblom, 1953; Lowi, 1971; Salamon, 1981). More recently the discussion of policy instruments is often centered on an individual’s behavioral change to solve policy issues. Through ‘nudging’ individuals are tempted to live healthier lifestyles and thereby reduce health risks which would lead to higher spending on healthcare (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Behavioral economics is a relatively new but very active field for policy analysis.

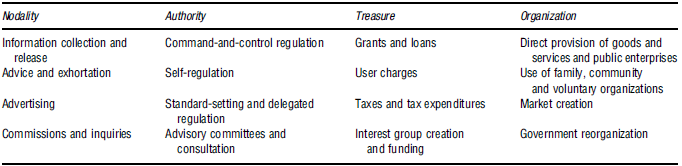

Nevertheless, the most intuitive and still powerful categorization was developed by Christopher Hood (1986). He distinguished between four different types of resources that governments could employ for achieving policy goals: Nodality, Authority, Treasure, and Organization (NATO) (Table 1).

Table 1 Policy instruments

Howlett, Ramesh, Perl, 116. Based on Hood, C., 1986. Tools of Government. Books on Demand.

Information-based policy instruments often take the form of public information campaigns which address citizens directly. They can either inform them about new government policies, entitlements, approaches or target behavioral change. Governments can also use information campaigns to change the perception of a problem or to influence the mood about a particular topic. This can facilitate or endorse other public policy changes. For instance, commissions and inquiries can be used to put a policy problem on the agenda and raise awareness for policy change. At first glance, information seems to be a weak policy instrument since it cannot enforce a particular behavior. However, many behavioral changes are based on an awareness of a situation. The perception of a particular problem is often an essential precondition for compliance with other policies.

Authority-based policy instruments are regulatory government tools that cover almost all policy fields. Regulation includes rules, norms, standards, directives and legislation. The violation of regulation is frequently punished by law. It is therefore a strong policy instrument in theory as long as the public authority is in a position to monitor compliance. If compliance cannot be observed, regulation is often ineffective. Compliance costs can also be high and outweigh the benefits. Self-regulation or delegated self-regulation can help to improve compliance when those actors who are the recipients of regulation can influence and participate in the setting of the regulation.

Financial instruments generally are very effective if used appropriately. Subsidies, transfers, grants and taxes have a direct effect on citizens’ behavior. Taxation on alcohol and tobacco reduces consumption and improves public health. Subsidies to farmers protect them from the effects of falling prices. Grants to service providers establish particular services. Financial instruments are, however, problematic as they can become politically entrenched. Once introduced, it is very hard to abolish transfers, tax-breaks or subsidies as people become dependent on them.

Organization-based instruments are provisions through the government directly or through agencies under governmental control. Schools, tax authorities, prisons hospitals, and armies are mostly under governmental control. For childcare and other social facilities, voluntary organizations can be supported through government agencies. Market creation through voucher schemes is another way of developing services. While public enterprises have largely been privatized throughout the last two decades, public–private partnerships have become more important. Government reorganization occurs in the context of privatization and the creation of new government agencies for supervising privatized utility providers or transport providers.

Very often governments employ a mixture of all instruments in order to implement public policies. For instance, vocational training in Germany is an important policy instrument that simultaneously keeps the rate of youth unemployment low and improves the skills of school leavers. In order to ensure a high rate of voluntary participation by firms to provide training places, the government runs information campaigns, gives tax breaks for hiring disadvantaged youths, enables and fosters firms’ self-regulation with regard to the content of training and runs public training facilities for those who do not find an apprenticeship. These different approaches are not chosen indiscriminately but with the expectation that they will reinforce each other. Often a range of policy tools is employed because the effectiveness of each individual tool is not known.

Which policy instrument will be chosen depends on a number of factors. First and foremost, policy choice depends on the broader institutional context of a country. There are different national approaches toward risk regulation, for instance, in the United States and Europe (Vogel, 2012). There are also differences in legal systems which make the use of regulation more or less appropriate. In some countries public ownership of firms or agencies is more accepted (as in France) than in others (for example in the UK). The use of tax-breaks is heavily used in the United States, where public spending is seen more critically, compared with Europe where both taxes and public spending is higher. Large scale changes often develop as an accumulation of small scale changes and major policy changes occur only very rarely in the context of political upheaval.

Politics and Institutional Constraints

Public policies are often path dependent and policy changes occur incrementally (Pierson, 2000). Once a particular problem is addressed by policies, the chances are high that future policies will be similar. As Aaron Wildavsky pointed out: the main predictor for a federal budget is last year’s budget (Pressman and Wildavsky, 1984). Once a particular public policy response to an existing problem has been developed, it is very likely that future responses will be at least influenced if not determined by it. A pension reform in the context of a Bismarckian pension system will not easily give up on pension insurance and move to a Beveridge public pension scheme. Rather, policy makers open up an avenue for another noninsurance pension pillar to lift the burden off the insurance-based pension.

This has several reasons: first, citizens’ expectations are shaped by previous policies. Second, policy makers themselves have a cognitive bias toward established responses. Third, political actors might have vested interests based on previous policies and fourthly, the costs for changing an established path continually rise even if the costs of an existing and unsuccessful policy might rise too. Peter Hall (1993) has distinguished between three different kinds of policy learning and has acknowledged the high barriers for fundamental policy change. Third order policy change, which involves a shift of paradigm as to how to interpret and solve a problem, occurs only after much experimentation and several crises, after which existing policies have been proven to have failed.

Besides path dependence and barriers for policy learning there are clear institutional effects on policy making. Not all public policies are equally likely in all institutional settings. Rather, different kind of political systems, political institutions and electoral rules have different effects on policy making. These effects are not well understood yet and research on institutional factors determining policies is still in its infancy (Immergut, 2006).

One influential study that looked at the effects of political institutions on public policies is Lijphart (Lijphart, 1984, 1999). The study distinguishes between consensus and majoritarian democracies. Political institutions in majoritarian democracies provide governments with a strong majority and the capacity to implement far-reaching policy changes which cannot be vetoed by other actors. In contrast, consensus democracies heavily constrain governments in their decision-making power. Variables that are used to classify political systems are the number of political parties, coalition governments, federalism and also the role of the central bank and constitutional courts. Lijphart correlates political systems with policy outcomes such as economic growth, inflation, social spending and citizen satisfaction. He comes to the conclusion that consensus democracies, which are mainly to be found in continental Europe, tend to be the kinder, gentler form of democracy (Lijphart, 1999).

A similar approach is pursued by Iversen and Soskice (2006) who use electoral rules as a major factor determining policy outcomes. They also divide modern democracies into two types: those with proportional representation and those with majoritarian electoral rules. In democracies with majoritarian electoral rules, we tend to find two-party systems. This is because losers of elections are heavily punished and small parties cannot survive. In a two-party system, the middle class voter has the choice to vote for a left-wing party which might tax the middle classes to spend on the poor or to vote for a right-wing party which constrains taxation. On balance, middle class voters will vote for the right, leading to lower levels of social spending in countries with majoritarian institutions. The evidence shows that majoritarian democracies have experienced far more years of conservative rule than of left-wing rule, as well as lower levels of social spending. Similarly but with different arguments, Persson and Tabellini, have argued that in proportional electoral systems politicians maximize votes (and not districts as in majoritarian systems) and tend to go for redistributive policies such as social spending or public pensions (Persson and Tabellini, 2002).

Other studies have looked at the capacity of other actors to constrain governments. Ellen Immergut has, for instance, identified veto points in the policy process, which can be used by opposing actors to stop a particular policy. Depending on the availability of veto points, some policies, such as comprehensive healthcare, might be prevented by special interest groups (Immergut, 1990). Similarly, George Tsebelis has identified veto players in the policy process. He argues that policy change will be more difficult when the number of veto players increases (Tsebelis, 2002).

Theories as to the effects of electoral rules and political institutions have been powerful for explaining redistribution and social spending and, therefore, the size of the government and the welfare state (Huber et al., 1993). They have been less influential for other policy fields and policy change. It is, however, currently undisputed that in advanced democracies there is a major difference between countries with majoritarian and proportional representation for social distribution.

Public Policy Outlook

Our knowledge about the effectiveness of policies and the role of public policy has vastly improved over the last 50 years. The scientific approach toward policies as well as a more systematic evaluation of existing public policies has created a wealth of knowledge of what works. The move toward evidence-based policy making and behavioral economics will improve our knowledge base even more. In a couple of decades, policy makers in advanced democracies will know exactly what the best approach for solving pressing social and political problems will be.

However, the most effective policies are still not the most likely to be adopted. In public health, a healthier lifestyle through exercise and nutrition is frustrated by producers and consumers of unhealthy products. Introducing taxes or banning sugary drinks have been very controversial and politically contested. The fight against the tobacco industry has been ultimately successful in the developed world while more smokers exist today due to an increase in the developing world. In environmental policy, the predominance of individual transport by car undermines global targets of lower carbon emissions. In global environmental policy, free-riding and collective action problems undermine common solutions. In education policy early childhood education still receives the least funding even though experts agree that early investment for children is highly effective. There are many more examples that prove that policy makers do not choose the best policy to address public concerns. Rather, political interests, power constellations and political institutions heavily influence the choice of public policies. The flaws in the democratic policy process which gives other interests, including a general skepticism toward government intervention in society and markets, an avenue for lobbying and intervention, has so far prevented a more systematic science-based policy approach.

Recently, public policies have also been increasingly influenced by private actors. Business and civil society actors are far more active in policy debates than they were before. Iron triangles of policy makers, where bureaucrats and experts jointly dominate a policy field have been replaced by a more fluid policy process. Governments control policies less now than they did in the past. They also use many more market-based policy instruments than before. This is not necessarily based on evidence but more often on general political motivation to include the private sector in the provision of services. Privatization and deregulation have created private interests in previously government controlled policy fields. These have created problems of their own which are still ongoing.

On the whole, the field of public policy is likely to further expand and professionalize. Modern societies are facing many problems which governments are expected to solve. Finance and trade, climate change, global migration, and health threats have evolved into global policy fields as crises can be contagious and are not confined to national borders. The application of existing knowledge to policy problems will remain a major issue for the years to come even though the exact form of policy research and application is likely to change.

References:

- Dahl, R.A., Lindblom, C.E., 1953. Politics, Economics and Welfare. Transaction Publishers.

- Deleon, P., 2006. The historical roots of the field. In: Moran, M., Rein, M., Goodin, R.E. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford University Press, United States.

- Dunn, W.N., 1994. Public Policy Analysis: An Introduction. Prentice Hall.

- Dye, T.R., 1972. Understanding Public Policy. Prentice Hall.

- Hall, P., 1993. Policy paradigms, social learning and the state: the case of economic policy making in Britain. Comparative Politics 25, 275–296.

- Hood, C., 1986. Tools of Government. Books on Demand.

- Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., Perl, A., 2009. Studying Public Policy: Policy Cycles and Policy Subsystems. Oxford University Press, Canada.

- Huber, E., Ragin, C., et al., 1993. Social democracy, Christian democracy, constitutional structure, and the welfare state. American Journal of Sociology 99, 711–749.

- Immergut, E.M., 1990. Institutions, veto points, and policy results: a comparative analysis of health care. Journal of Public Policy 10, 391–416.

- Immergut, E.M., 2006. Institutional constraints on policy. In: Moran, M., Rein, M., Goodin, R.E. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford University Press, United States.

- Iversen, T., Soskice, D., 2006. Electoral institutions and the politics of coalitions: why some democracies redistribute more than others. American Political Science Review 100, 165–181.

- Klein, R., Marmor, T.R., 2006. Reflections on policy analysis: putting it together again. In: Moran, M., Rein, M., Goodin, R.E. (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford University Press, United States.

- Lasswell, H.D., 1951. The policy orientation. In: Lerner, D., Lasswell, H.D. (Eds.), The Policy Sciences: Recent Developments in Scope and Method. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, California.

- Lijphart, A., 1984. Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty One Countries. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Lijphart, A., 1999. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale University Press, New Haven; London.

- Lowi, T.J., 1971. The Politics of Disorder. Basic Books Inc., New York; London.

- Moran, M., Rein, M., Goodin, R.E., 2006. The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford University Press, United States.

- Persson, T., Tabellini, G.E., 2002. Political Economics: Explaining Economic Policy. MIT Press.

- Pierson, P., 2000. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. American Political Science Review 94, 251–267.

- Pressman, J.L., Wildavsky, A., 1984. Implementation: How Great Expectations in Washington Are Dashed in Oakland: Or, Why It’s Amazing that Federal Programs Work at All, This Being a Saga of the Economic Development Administration as Told by Two Sympathetic Observers Who Seek to Build Morals on a Foundation of Ruined Hopes. Colegio Nacional de Ciencias Políticas y Administración Pública: Fondo de cultura económica.

- Radaelli, C.M., 1995. The role of knowledge in the policy process. Journal of European Public Policy 2, 159–183.

- Salamon, L.M., 1981. Rethinking public management: third-party government and the changing forms of government action. Public Policy 29, 255–275.

- Thaler, R.H., Sunstein, C.R., 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Tsebelis, G., 2002. Veto Players. How Political Institutions Work. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

- Vogel, David, 2012. Politics of Precaution: Regulating Health, Safety and Environmental Risks in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press, NJ.

- Young, J., Mendizabal, E., 2009. Helping Researchers Become Policy Entrepreneurs: How to Develop Engagement Strategies for Evidence-Based Policy-Making. Overseas Development Institute.